In his esteemed collection of rigorously authenticated Prophetic traditions, Imam al-Bukhārī records the statement of the Prophet (upon him be peace): “The best deeds in the sight of God are those that are performed with the greatest consistency.”

The American Learning Institute for Muslims (ALIM) has been hosting its annual summer program for a quarter century. Needless to say, much has changed in 25 years. However, ALIM has demonstrated incredible consistency. We’ve remained committed to our mission. We empower Muslims through Islamic literacy.

0 Comments

By: Ustadh Ubaydullah Evans Scholar-in-Residence, ALIM As a signifier of commitment to progressive values, the terms “diversity and inclusion” are nearly ubiquitous. The past decade or so has witnessed “diversity and inclusion” move from the Affirmative Action inspired charters of schools and businesses to a vibrant part of our media, art, and vernacular cultures. Put differently, we no longer only expect diversity and inclusion where we work or study; it’s something we’ve come to seek more broadly. Taken at face value, this shift toward plurality should inspire American Muslims with great satisfaction. Our faith affords inter- religious/cultural exchange and ultimately familiarity, spiritual value. The Qur’ān proclaims:

By: Ustadh Ubaydullah EvansALIM Scholar-in-Residence  Dr. Sherman Jackson is very eloquent, mashallah. In fact, so appreciated is his ability to “turn a phrase” that we jokingly use the term “Jacksonian” to describe the rhetorical flourishes for which he’s known. However, the most eloquent I’ve ever heard him is in response to a question about the “essence of Ramadan.” For Dr. Jackson, such a broad, open-ended question was like a pitch right down the middle of the plate. So in his simple response, “Ramadan is about being hungry” he appeared to bunt. A slight chuckle could be heard among the audience. For many, he had either ironically or jokingly stated the obvious.

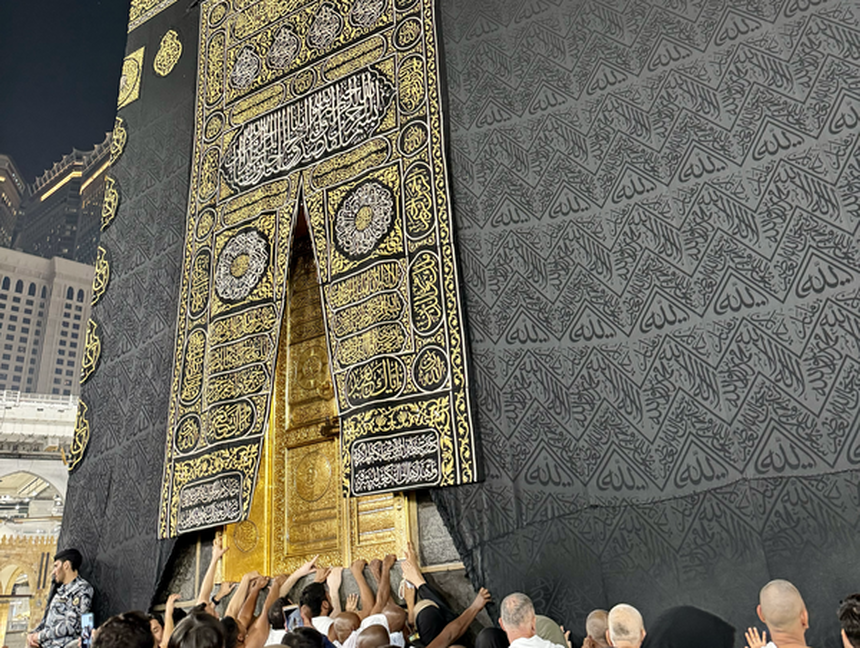

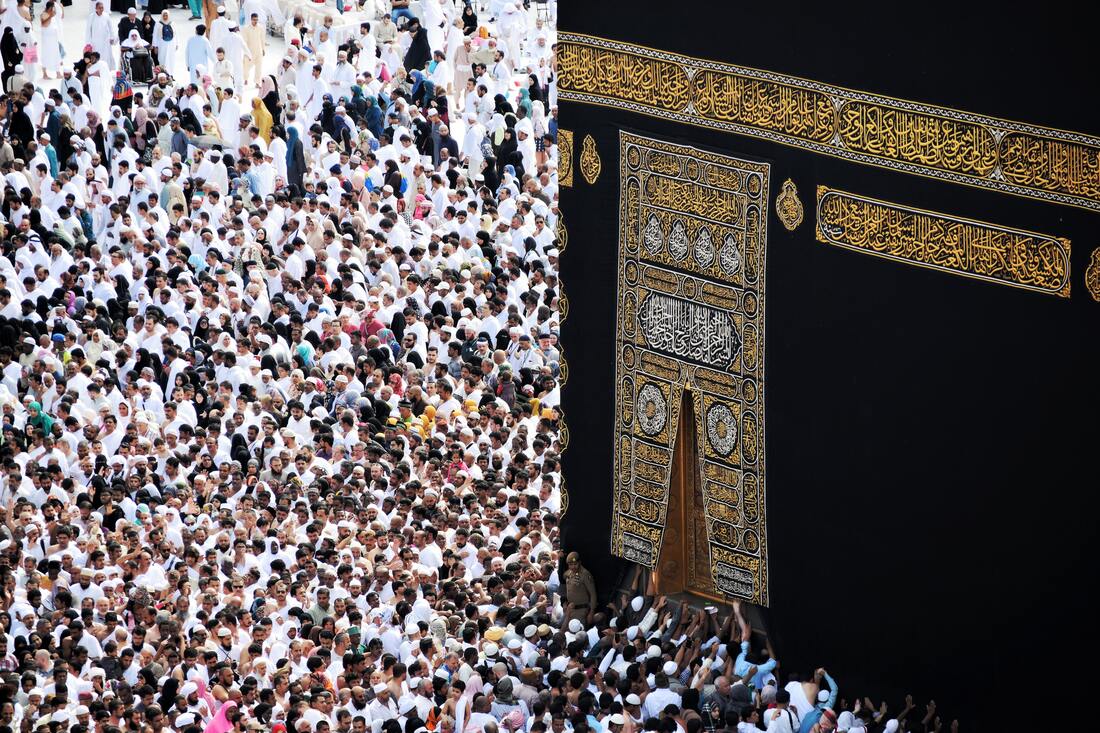

Hunger is undoubtedly our most primal urge. It is at once the greatest unifying factor within our humanity and the source of our greatest disparity. And for all that could be correctly said concerning our advocacy around hunger: the obligation to fight it, to repudiate the greed that subjects so many of our fellow men and women to it involuntarily, the unacceptable callousness with which we turn a blind eye to those afflicted by hunger, it remains a perennial human universal. by: Ustadh Ubaydullah EvansALIM's First Scholar-in-Residence Landing at King Abdulaziz International Airport was the penultimate stage of our journey and already the adrenaline was starting to course through my veins. It was between the time of the Afternoon Prayer (Dhuhr) and the Late Afternoon Prayer (Asr). The weariness of travel, and at this point we had been traveling for an entire day, gave way to child-like ebullience. I was giddy. As my talbiya grew in intensity and purpose, I scanned my surroundings and took in the environment. This was the desert; barren, rocky, arid, and isolated. And yet there we were, with a million other pilgrims, voluntarily converging on this otherwise unremarkable destination. I reflected upon the verse:

By: Ustadh Ubaydullah evansALIM Core Scholar, Scholar-in-Residence When the question is: What book initially piqued your interest in Islam? Surprisingly, the Qur’ān (in any of its various translations) is not the most referenced book by Americans who eventually embrace Islam. That distinction actually belongs to the Autobiography of Malcolm X.

In fact, it has always been my contention that Malcolm fits perfectly into the traditional Islamic discourse around wilāya (an idea similar to sainthood within Roman Catholicism sans the beatification and canonization) and karāmāt (miracles). Within this understanding, Malcolm is a walī and the influence of his autobiography is his miracle. In all, I have personally encountered over 100 Muslims who have cited Malcolm’s story as their gateway into Islam—and I’m sure there are many more. By: Ustadh Ubaydullah EvansALIM Core Scholar, Scholar-in-Residence One of the most insightful religious reflections I ever heard was mentioned by an atheist. During the Q and A that directly followed my lecture, a questioner from the audience rose to speak. He was a middle-aged white man of slender build, dressed in business casual (chinos and a plaid button down shirt) clothing, and wearing glasses. I got the sense that he was a member of the faculty at the small college at which I was presenting. After thanking me for my remarks, which, if I recall correctly, were about Islam and Post-Modernity or something like that, he sought my permission to venture slightly off topic and ask a ‘personal’ question. Not knowing what to I expect, I forced a laugh and said, “well, it depends how personal.” After granting him permission, he identified himself as “an atheist but a seeker,” he then said, “I thought your remarks about religion were balanced. I’m clear about your conviction but it didn’t appear that you were attempting to evangelize [sic] the audience. I feel compelled to ask, what is the most challenging aspect of being a person of faith in the modern age?” The question was pithy and I don’t think any non-Muslim had ever posed it to me in such direct fashion.

by: Dr. Muneer FareedALIM Core Scholar Where are the Leaders!

This latest attack on Ghazza raises difficult questions pertaining to leadership, and brings into sharp relief, once again, the tension between the leaders we demand and those we deserve. We demand of our leaders that they speak truth to power, when in fact, we should try and limit our demands to that which plays to their strengths, bearing in mind that strengths vary from person to person. Unfortunately, some of our leaders are equally to blame: instead of trying to punch above their weight they too should limit themselves to their strengths, and work on curbing their urge to bask in the limelight. BY: USTADH UBAYDULLAH EVANS ALIM Core Scholar and Scholar-in-Residence Nicholas Grant’s Winning our Freedoms Together: African Americans and Apartheid, 1945-1960 is a transnational study of white supremacy and Black resistance. As is indicated by its title, this survey captures the political and cultural ties of Blackamericans to the anti-apartheid movement. The Trans-Atlantic, Black internationalist allyship formed among Blackamericans and South Africans amplified the efforts of freedom fighters within both struggles. The most interesting aspect of Grant’s analysis is his presentation of the organic way in which this nexus developed. It engaged intellectuals and radicals but also made deep impacts within Blackamerican vernacular culture.

By: Dr. Sherman A. JacksonALIM Core Scholar I have no problem condemning the killing of innocent civilians, wherever and whoever they might be. This is among the dictates of the Qur’ān itself. “O you who believe, be upholders of justice, witnesses for God, even if against yourselves.”

Once, the Prophet (SAWS) sent a group of Companions on a reconnaissance mission and gave them explicit instructions to do nothing but gather intelligence. They saw a Qurayshi caravan, however, and decided to attack it. Quraysh was outraged and set out to scandalize the Prophet, as this attack took place in one of the Forbidden Months, which banned anyone from attacking anyone. The Qur’ān refers to this incident in Sūrat al-Baqarah, 2: 217: “They ask you about fighting in the Forbidden Months. Say, fighting in them is an abomination. But impeding the path to God and rejecting Him, as well as the Sacred House, and turning its people out is an even greater abomination. And subjugation is worse than killing (wa ‘l-fitnatu akbar min al-qatl).” By: Ustadh Ubaydullah EvansALIM Core Scholar and Scholar-in-Residence I have always maintained that our context makes a full embrace of the Prophet Muhammad (upon him be peace) difficult. Within our sacred history, Jesus Christ of Nazareth (upon him and his blessed mother be peace) is the direct predecessor of the Prophet Muhammad (upon him be peace). Relative chronological proximity as well as being the central religious figures of the two largest religious communities in the world have linked inextricably the Christ and the Prophet (upon them be peace).

by: Ustadh Ubaydullah EvansALIM Core Scholar and ALIM's first Scholar-in-Residence The power of charisma is undeniable and often irresistible. Whenever our community witnesses the painful “fall from grace” of a religious figure, there is always a vocal faction calling out “cults of personality” and urging commitment to principle over people. On the one hand, this is appreciable. The Qur’an and traditions of the Prophet (upon him be peace) are replete with warnings about the injustice that accrues when focus is unduly placed on personalities as opposed to principles. On the other, while the virtue of qiṣṭ (moral commitment to justice) should guide our adjudication, it certainly cannot be said to account for the heartbreak we feel at the knowledge that one of our leaders has morally failed.

By: Ustadh Ubaydullah EvansALIM Core Scholar and ALIM's First Scholar-in-Residence "Diversity and inclusion" are more than just buzzwords in our contemporary society. They represent a profound shift in how we perceive, engage with, and value differences in an increasingly globalized world. Originating from Affirmative Action policies that sought to redress historical injustices in educational and corporate environments, these terms have evolved to encompass a broader societal ethos. They have transitioned from being mere institutional objectives to becoming deeply ingrained societal values that influence our daily interactions, media representations, and cultural expressions.

BY: USTADH UBAYDULLAH EVANSALIM Core Scholar and ALIM's First Scholar-in-Residence The greatest liability of a good story is familiarity. Even the best stories are rendered a little less stirring with the passage of time and frequent repetition. Hakim Archuletta, a traditionally trained Islamic healer and homeopathy specialist, once described a good story as following life’s natural rhythm of contraction (qabḍ) and expansion (baṣṭ). The experience of listening intently, being wound up bit by bit, the tension (contraction) growing with the suspense, only to find relief (expansion) in the resolution is what holds our attention when listening to stories. As such, when suspense is lacking—because the outcome of the story is known—being present requires more intentionality. I’ve been told that the wheat is separated from the chaff among actors by a performer’s ability to completely act as if the story is unfolding before their character in real-time, in spite of their knowing the entire script.

BY: USTADH UBAYDULLAH EVANS “And never have We sent forth any apostle otherwise than [with a message] in his own people’s tongue” – Quran 14:4.

“England and America are two countries separated by the same language” – George Bernard Shaw. In twenty-first-century America, speaking the moral language of normative Islam is tricky, to say the least. On the one hand, the current generation of Muslim Americans (in contrast to their immigrant forebearers) have now mastered the various idioms of colloquial American English along with its various cultural references, both high and low. On the other hand, the language of our ethics seems more foreign and garbled to mainstream America than ever. Like a well-meaning but embarrassingly naïve American tourist abroad, we often think that if we just raise our voice, speak slowly, and over-enunciate our words, people will eventually understand us: “WE BELIEVE IN TRADITIONAL RELIGION. WE BELIEVE THAT OUR SCRIPTURE IS DIVINE SPEECH AND THAT WE MUST CONFORM ALL OF OUR ACTIONS TO THE WILL OF GOD, NOT LEAST OUR SEXUAL MORES.” Those fluent in the language of Tradition appreciate the nuanced connotations of such words; those who have grown up speaking a more modern language, however, just stare, half-amused and half-perplexed. But, whereas a generation ago, this socio-linguistic divide between Muslim Americans and mainstream society was taken for granted, the Muslim community itself is now unable to effectively talk to each other. As Shaw noted about England and America, the very fact that we are all ostensibly from the same highly specific background – Muslim and American – means that, while the words streaming forth from our mouths are ostensibly the same language, that very superficial commonality hinders actual communication even more than if we were speaking Chinese and Russian to one another. By: Ustadh Ubaydullah EvansALIM Scholar-in-Residence Recently, a dear friend sent me a link to an article about Hamtramck. The article highlighted the city council, which is comprised of all self-identified practicing Muslims, and the general population of the city which is also majority Muslim. The tone wasn’t alarmist, i.e. “The Shari’atization of America.” Nor was it an expression of Islamic triumphalism, i.e. “Hamtramck has become Dar al-Islam and Relocating there is a Religious Obligation.” Quite the reverse, the article struck me as relatively objective and expository. However, in covering some of the scenes of daily life there the journalist did select evocative descriptions of public Adhāns (call to prayer), veiled women, food carts, Arabic language billboards, etc.

|

|

stay connected

@alimprogram

PO Box 871785 Canton, MI 48187

(734) 956-0698

(734) 956-0698

2024 © American Learning Institute for Muslims. All rights reserved.

ALIM is a 501(c)(3) organization. All donations are zakat-eligible and tax deductible. Our EIN is 38-3633579.

Zelle: [email protected]

Terms of Service | Privacy Guidelines | Sign Up for ALIM Emails I Get ALIM Text Alerts

ALIM is a 501(c)(3) organization. All donations are zakat-eligible and tax deductible. Our EIN is 38-3633579.

Zelle: [email protected]

Terms of Service | Privacy Guidelines | Sign Up for ALIM Emails I Get ALIM Text Alerts

RSS Feed

RSS Feed