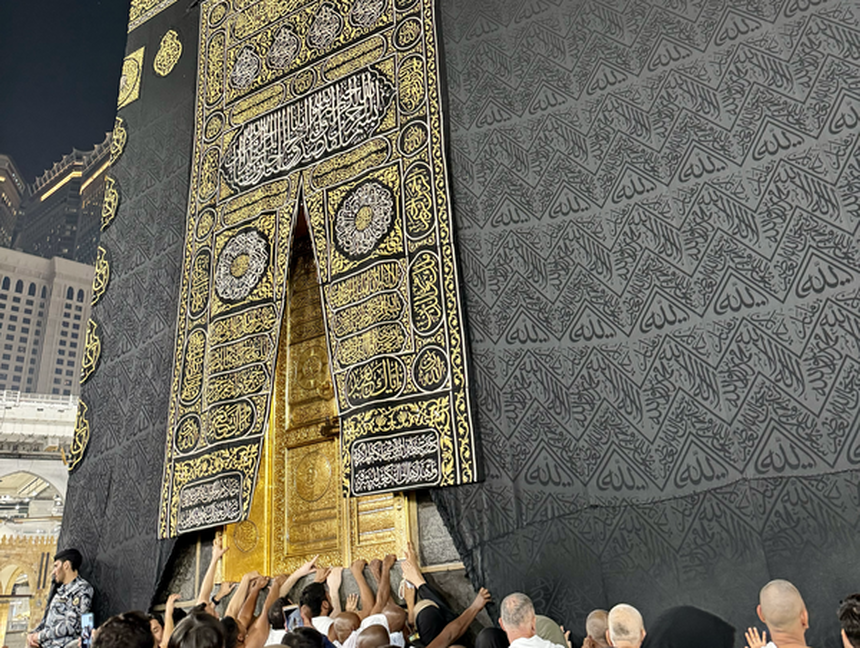

By: Ustadh Ubaydullah evansALIM Core Scholar, Scholar-in-Residence When the question is: What book initially piqued your interest in Islam? Surprisingly, the Qur’ān (in any of its various translations) is not the most referenced book by Americans who eventually embrace Islam. That distinction actually belongs to the Autobiography of Malcolm X. In fact, it has always been my contention that Malcolm fits perfectly into the traditional Islamic discourse around wilāya (an idea similar to sainthood within Roman Catholicism sans the beatification and canonization) and karāmāt (miracles). Within this understanding, Malcolm is a walī and the influence of his autobiography is his miracle. In all, I have personally encountered over 100 Muslims who have cited Malcolm’s story as their gateway into Islam—and I’m sure there are many more. Invariably, when asked, “what was it about that book, what did it do for you?” we all reference the chapter entitled “Mecca.” I’m unable to put my finger on what struck me as the most evocative bit; either the manner in which the pilgrimage forced him to reexamine his earlier racial separatism or how his theretofore experience with Islam had been limited to that of redemptive moral teaching. It was at Hajj, that Malcolm came face to face with the rich liturgy and ritual practice of Islam. Nonetheless, the cumulative impact of Malcolm’s recollection and Alex Haley’s prose was Makkah being ensconced in my mind as a site of spiritual longing. I thought that my Makkah should resemble Malcolm’s: His journey was captured at the end of an Augustinian confessional narrative, the ultimate denouement that tied all the strands of his story together. And because I couldn’t conceive of a trip to Makkah for myself that would match Malcolm’s, I indefinitely postponed making Hajj or Umrah. My reasons for this were twofold. First, I was concerned about my own spiritual preparedness. The thought of Umrah was daunting. I’ve been a Muslim for nearly a quarter century and presence of mind during communal acts of worship is still a challenge. It’s difficult to explain; I sometimes assume the role of a disembodied observer of the “Muslim religious experience” when worshiping in unfamiliar congregational spaces. At times, I can hover above the space with the dispassionate vantage of an anthropologist instead of the acutely present worshiper to which I aspire. With regard to Hajj and Umrah, I was forewarned: The manāsik (pilgrimage rites) represent a modality of worship with which many Muslims are unfamiliar: Kinetic not methodical and still, characterized by fervor as opposed to solemnity and sonically explicit not sober. There would be a lot of new phenomena to process. I couldn’t be Malcolm and Richard Francis Burton at the same time! Secondly, I was concerned about my experience of the Ummah (global Muslim community). Indeed, I had heard stories of fraternity, generosity, and humanity but I had also heard stories of racism, fraud and sexual assault. As a convert to Islam, I’ve learned to manage my disappointment with the Muslim community—just as I’m sure my community manages its disappointment with me. However, in a way I would struggle to put into words, I needed Makkah and Madinah to fulfill their promise. It was emotional. If in the past, I was given the ultimatum of visiting the Haramain and experiencing them as a disappointment or never actually visiting but retaining for them a spiritually uplifting place within my imagination, I would have chosen the latter. As such, when our team at the American Learning Institute for Muslims (ALIM) began planning an educational Umrah trip loosely themed on the Prophetic Biography (Sirah), I was ambivalent. Nonetheless, as our departure neared, my ambivalence gave way to excitement. My eldest daughter, Aasiyah, would be accompanying me. We would leave on the 16th of December and travel with a group of close to 40 people which would include Drs. Sherman Jackson and Muneer Fareed as teachers. The first leg of the trip was prosaic—A Turkish Airlines flight from Chicago to Istanbul. However, things began to get interesting in Istanbul. Arriving to the airport at the time of the dawn prayer, we entered the changing rooms designated for pilgrims. Standing in the dressing room, staring at myself in the mirror, I began to sense the significance of the journey my daughter and I were taking. We were traveling back in time. I had entered a state of iḥrām. To be sure, retaining a religious outlook and being a Muslim in modern America is trying. In my estimation, most of the trial is from wearing the tincture of a culture that has been shaped in ways material (scientific and technological) and moral that suggests that religion is passé. The two white, unstitched pieces of terry cloth were like Doc and Marty’s DeLorean. Wrapped in them, the accoutrement of the modern age which separates us from our pre-modern forbearers diminished in importance. Iḥrām was continuity. I am human like they were human; same grappling with mortality, same existential dread and hope for salvation, in the same two unstitched garments. Traversing Istanbul International Airport, a few things surprised me: First, the iḥrām provided much more secure and comfortable coverage than I anticipated. I wasn’t nearly as cold or self-conscious as I had expected. Two, I love clothes and personal appearance is an area in which I apply myself with intentionality. This wasn’t a surprise. The surprise, rather, was noticing the delicate interplay between my appearance and my demeanor. In other words, just as a jacket and tie or sportswear elicits gestures of gentility or athleticism that seem to naturally accompany them, so too does iḥrām. As a pilgrim my gait became a little less lively, tone of voice less boisterous, presence more self-contained. And lastly, Aasiyah really impressed me. In the lead up to Istanbul, she had enjoyed her normal medley of Drill music, podcasts, and murder mysteries. As a father, I wanted my babygirl to grasp the spiritual significance of the moment but not in a performative way which might make me feel like I was directing things correctly but could result in her feeling less ownership of the moment. Alhamdulillah, without me saying anything, Aasiyah understood the significance of the moment and set aside her normal fare to focus on heightening her devotion. Our plane took off bound for Jeddah…

Since then, he has studied at Chicagoland’s Institute of Islamic Education (IIE), in Tarim, Yemen, and Al-Azhar University in Cairo, Egypt, where he is the first African-American to graduate from its Shari’a program. Ustadh Ubaydullah also instructs with the Ta’leef Collective and the Inner-City Muslim Action Network (IMAN) at times.

As the ALIM Scholar-in-Residence, Ustadh Ubaydullah is a core instructor at the ALIM Summer Program. He teaches History of Islamic Law, Shama'il, and Aphorisims of Ibn Ata'illah along with other courses.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|

stay connected

@alimprogram

PO Box 871785 Canton, MI 48187

(734) 956-0698

(734) 956-0698

2024 © American Learning Institute for Muslims. All rights reserved.

ALIM is a 501(c)(3) organization. All donations are zakat-eligible and tax deductible. Our EIN is 38-3633579.

Zelle: [email protected]

Terms of Service | Privacy Guidelines | Sign Up for ALIM Emails I Get ALIM Text Alerts

ALIM is a 501(c)(3) organization. All donations are zakat-eligible and tax deductible. Our EIN is 38-3633579.

Zelle: [email protected]

Terms of Service | Privacy Guidelines | Sign Up for ALIM Emails I Get ALIM Text Alerts

RSS Feed

RSS Feed