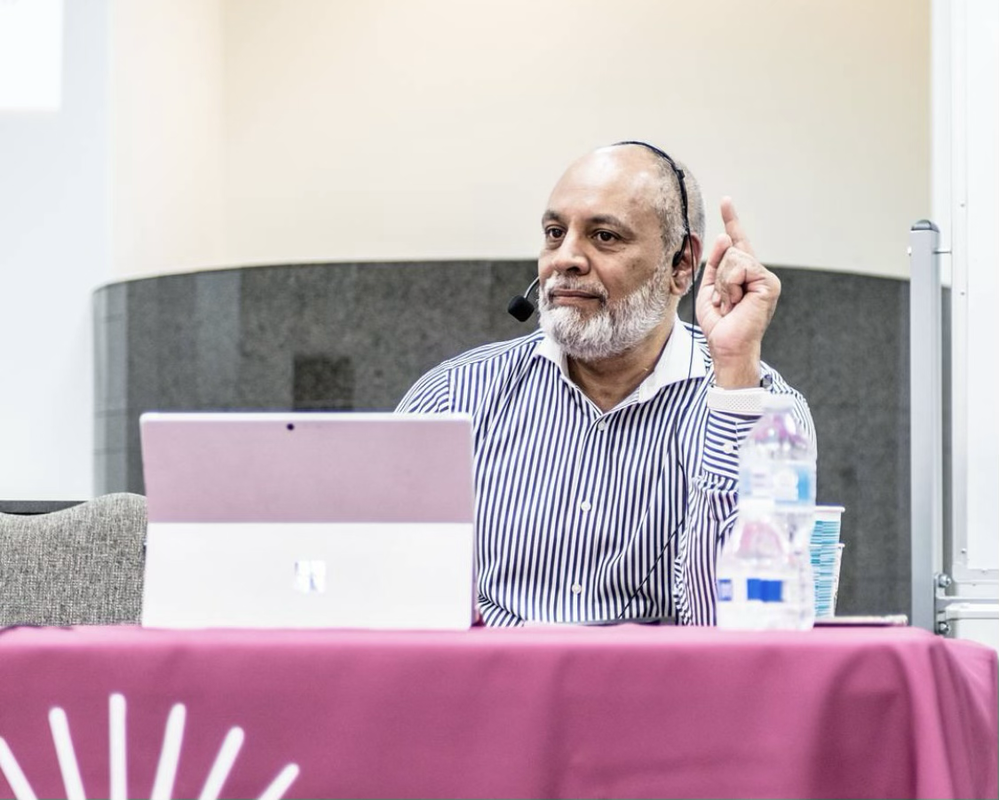

by: Dr. Muneer FareedALIM Core Scholar Where are the Leaders!

This latest attack on Ghazza raises difficult questions pertaining to leadership, and brings into sharp relief, once again, the tension between the leaders we demand and those we deserve. We demand of our leaders that they speak truth to power, when in fact, we should try and limit our demands to that which plays to their strengths, bearing in mind that strengths vary from person to person. Unfortunately, some of our leaders are equally to blame: instead of trying to punch above their weight they too should limit themselves to their strengths, and work on curbing their urge to bask in the limelight.

0 Comments

The acronym, ALTICALSA, I imagine, would not resonate too loudly with many Muslims in America, and for good reason. In the first place, the artifacts housed in this section of the Metropolitan Museum of Art spring not to mind as telling historical reminders of Islam’s potential beyond bombs and mayhem. And as Mehri Khalil discovered recently, the curators of this and other renowned museums have added to this disjuncture between Islam and aesthetics by rechristening these very sections of their libraries. The Galleries of Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia and later South Asia (ALTICALSA) were until September 11, 2001 more elegantly titled the Islamic Galleries. Since then, almost all references to Islam in these galleries have been replaced by nomenclatures that say as much about our changing political landscape as they do about Islam and aesthetics.

Some months ago Salzburg, Austria, the birth place of Mozart, and the city of churches and bell-towers, was chosen to showcase a 10 day Spiritual Overture. Zubin Mehta, the celebrated Indian conductor, led the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra in a symphony centering on the Holocaust, and appropriately titled “Revival of the Dead”. In the coming year the focus will switch to Buddhism and then in the years ahead to other religions. This particular spiritual musical ensemble, we learn, was based on artistic director Alexander Pereira’s belief that humanity is reaching out beyond rationalism to an idealism best articulated through aesthetics in general, and music in particular. And he’s not alone. Jane Moss, vice president for Programming at New York City’s Lincoln Center and self-described ‘secular mystic’ believes people are ‘looking for larger experiences in a cyber-world’. Humanity, Moss argues, is becoming desensitized by the surrealistic tendencies of modern technology. And in the absence of organized religion—which many in the industrialized world now turn their backs on—only music remains, she says, as humanity’s “live experience left in the world.”

Introduction

A secular aesthetics is fast replacing religion as the go-to spiritual forum of the 21st century. Humanity’s post Enlightenment journey, first through modern rationalism, then through scientific empiricism and more recently, anarchic relativism has left us turning wearily to an aesthetics that offers, not just to lighten the unbearable ennui of this material existence, but to do so along with fellow sojourners unburdened by the weight of tradition. Aesthetics offers today’s secular citizenry a chance to bond with each other in a communal identity that, unlike the religious, is both reassuringly realistic, and socially inclusive. Aesthetic spirituality differs from religious spirituality in two significant ways: it emphasizes beauty rather than truth, and more importantly, replaces traditional forms of devotion with a philosophy that plays out in the public forum not as worship, but as art. Our collective ambivalence towards “the right to bear arms” is aptly summed up in the following tweet that went viral after the shooting at Sandy Hook elementary school: “One guy tries to use [a] shoe bomb and everyone at the airport now has to take shoes off. 31 school shootings since Columbine, but no change.” Over the years, legislators on both sides of the political spectrum have avoided serious reforms as the NRA has grown into one of the most influential lobbies in Washington, DC. In political campaigns, candidates generally shy away from substantive discussion around gun control, opting instead to debate our romanticized “right to bear arms.” The fact is, however, that we have outgrown the 2nd Amendment.

The Black community in America is now led by what some call the post-civil rights generation. These heirs to America’s newest cultural ideal, the diversity movement, graduate in significant numbers from America’s elite colleges and universities and occupy plum jobs in industry and the civil service. College admission policies together with corporate recruitment policies are increasingly driven by the quest for diversity, by which is meant, not the mere assortment of persons who together represent humanity’s cultural variety or ethno-racial multiplicity, but rather a quantitative array of human beings who fit certain racial and ethnic profiles.

To the extent that they failed to use their pulpit to bully their congregants into living by Islam’s own human rights culture, the `ulama certainly have been remiss. But beyond the confines of the mosque clerical authority was severely curtailed by forces beyond `ulama control. Perhaps the most subversive of these forces came from Europe where earlier, the Enlightenment had trumped Church authority. In time, and as a result of colonization, all traditional societies, including the Islamic, were infected by the European bug, and thus began society’s awkward oscillation between tradition and change. This was particularly onerous on the `ulama as custodians of a tradition which centered itself on revelation rather than human creativity, and whose social values hearkened unto the Medina of the Prophet rather than John Rawls’ overlapping utilitarian future.

What is it about law and religion that embroils jurists and theologians in deep, sometimes acrimonious discussions that critics say deliver less than was promised? Well, for one, they both make progress without making discoveries. Their aim, in other words, is rarely to unearth the unknown in their particular vocations, but rather, to focus on that which is familiar, and yet escapes notice. And that is not entirely an exercise in futility! To quote Wittgenstein, throwing a different light on the familiar, has epistemic value as well, if only because, “the aspects of things that are most important for us are hidden because of their simplicity and familiarity”. (One is unable to notice something – because it is always before one’s eyes). The other similarity that law and religion share, and upon which I will focus more attention—with particular reference to Islam—is that they are both in their own ways quite traditional.

Some have called Cornel West’s scathing critique of Barack Obama petty, while others—including some in the Muslim community—argue that America would be better off without four more years of Barack Obama. Which is not to say that either West or disgruntled pockets within the Muslim community prefer Romney over Obama, but only that his less than progressive politics, they believe, would do little to alter the status quo. So, what changed?

In recent years, the idea of Shariah compliance has taken firm root in the business world and been applied in multiple spheres; everything from Shariah-compliant mortgages to Shariah-compliant hedge funds are growing increasingly popular. The Economist dubbed the phenomenon “sharianomics.”

Today, as Islamic financing grows exponentially because many more Muslims are mindful of the Shariah aspects of financial transactions, I would like to remind them that there is an often ignored social justice aspect to such financing as well. As Dr. Kavilash Chawla points out in his article “Islamic Venture Philanthropy” ;Business Islamica, June 20071, as the world tilts away from state power towards corporate power, the ability of public institutions and aid organizations to address poverty across the world grows weaker. Because of this tilt, the private financial sector is being called upon increasingly to do more to alleviate the suffering of the poor: I believe that Islamic financing is uniquely positioned to do just that, but only if it broadens its application of the Shariah. That material prosperity and religious belief are intertwined would seem to have been an abiding leitmotif of most major faiths and ideologies. One prophetic tradition, for instance, presents this very idea, thus: “if poverty is left unchecked, then it may well lead to disbelief!” And when Marx calls religion “the sigh of the oppressed, the heart of the heartless, the soul of the soulless, and the opium of the people”, he too makes the link, albeit for altogether different reasons. And then there’ s Weber’s ‘Protestant work ethic” which, according to him, is how Christian Europe turned work into dogma, and how, some say, the West got so far ahead of the rest.

Now comes empirical research to corroborate these views in ways that give religion in general an all new resonance in an otherwise secular world; and perhaps for Islam, in particular, an all new role in the economic lives of its adherents. A recent survey conducted by the Hudson Institute’s Center for Religious Freedom found that the weaker the economic conditions of a country the more intolerant its religious policies are likely to be—and vice versa. Thus, countries with poor economic records like Burma, Iraq, Bangladesh, Mauritania, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Eritrea, Vietnam, etc., also happen to have equally poor human rights records. Citizens of such countries are denied the right to live out their consciences, believe as they see fit, and practice their faiths in harmony with the national good. Not all countries admittedly fit this profile: some, like Saudi Arabia have relatively sound economies with high levels of religiosity—but with poor human rights records. This, researchers stress, is not proof that such a mix works, but rather, that economic performance in this case is quite unrelated to internal modes of production. |

|

stay connected

@alimprogram

PO Box 871785 Canton, MI 48187

(734) 956-0698

(734) 956-0698

2024 © American Learning Institute for Muslims. All rights reserved.

ALIM is a 501(c)(3) organization. All donations are zakat-eligible and tax deductible. Our EIN is 38-3633579.

Zelle: [email protected]

Terms of Service | Privacy Guidelines | Sign Up for ALIM Emails I Get ALIM Text Alerts

ALIM is a 501(c)(3) organization. All donations are zakat-eligible and tax deductible. Our EIN is 38-3633579.

Zelle: [email protected]

Terms of Service | Privacy Guidelines | Sign Up for ALIM Emails I Get ALIM Text Alerts

RSS Feed

RSS Feed