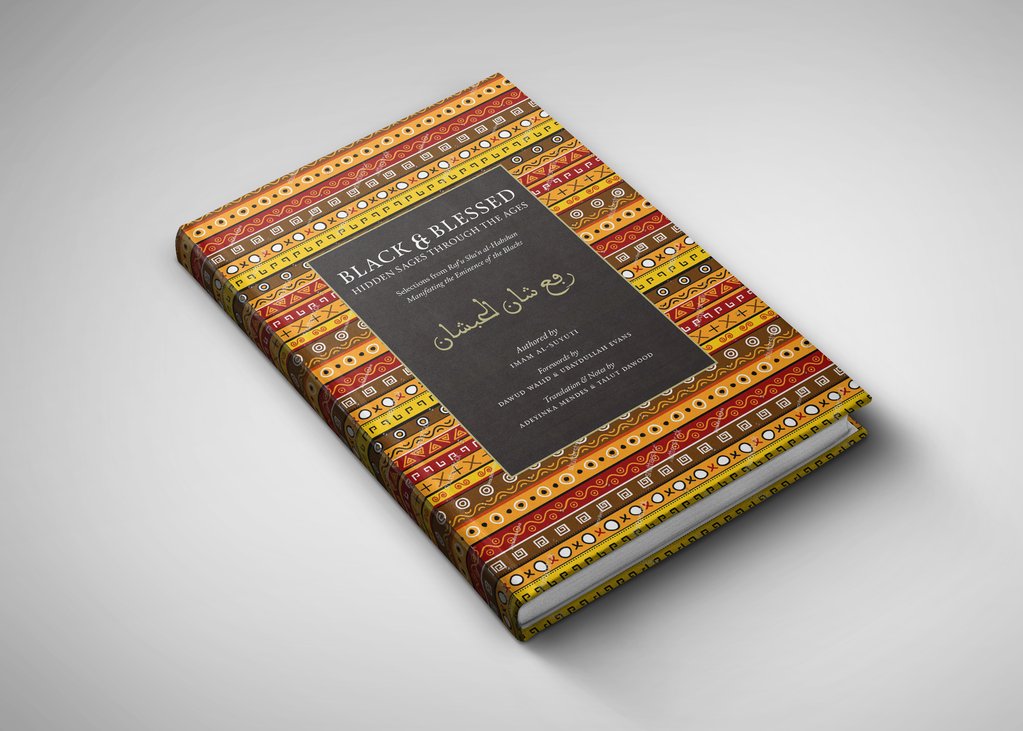

Ustadh Ubaydullah EvansFor some, Imam Muhammad Adeyinka Mendes’s beautifully rendered translation of The Spirits of Black Folk: Sages through the Ages will prompt them to ask: “Why is this necessary?” They would not be out of place to raise such a question. Many Muslims view the current conversation around race in our community with a jaundiced eye. In asking “why”, I do not believe they intend to invalidate the grievances of Black communities. Nor do I assume them to be enthralled to certain manifestations of anti-Blackness that instinctively respond with dismissal to any celebration of Black people. To be honest, I think they are justifiably anxious. It requires only a modicum of imagination and dialectical skill to realize the problematic implications of the way in which race and identity are discussed in our society. “How will such a specific focus on Blackness—itself socially constructed and incidental—alter our understanding of transcendent Truth?” they ask with great concern. And I appreciate this. However, I invite them to consider the following: many of us await Imam Muhammad’s translation with great anticipation. We are vindicated at finally hearing the august voice of FOREWORDS XVI THE SPIRITS OF BLACK FOLK classical Islamic scholarship addressing our people. And yet we too ask: “Why is this necessary?” Modern scholarship on race, racism, and white supremacy has made invaluable contributions to our understandings of these phenomena. Citing The Souls of Black Folk, the 118-year-old magnum opus of W.E.B. Du Bois, almost feels like an act of ingratitude toward contemporary scholars such as Su’ad Abdul Khabeer, Sylvia Chan-Malik, Jamillah Karim, Junaid Rana, and others for their much more recent work in critical and race studies. Nevertheless, it is the old master who best captures my sentiment. Responding to the “problem of the color line” in Souls, Du Bois writes: Between me and the other world there is ever an unasked question: unasked by some through feelings of delicacy; by others through the difficulty of rightly framing it. All, nevertheless flutter round it. How does it feel to be a problem? How does it feel to belong to the only community whose “dysfunction” is referenced whenever the issue of inequality is raised? How does it feel to deliver numerous lectures that might as well be subtitled, “On the Humanity of Black People,” even though Black humanity is a product of Divine fiat? In that vein, how does it feel to have one of your most broadly learned colleagues expend his precious mental energy to translate a work of lesser significance when considering the total corpus of the prolific Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī? So prodigious was the output of the great Imam that he was referred to as Ibn al-Kutub (the son of books)—nearly 500 titles have been credited to his authorship! How does it feel to know that many English read- FOREWORDS XVII ers will not be introduced to this great polymath via his works of Qur’anic exegesis like Al-Durr Al-Manthūr, or works on legal theory like Al-Ashbā’ih wa Al-Naẓā’ir? Why, pray tell, is this necessary? There is no pride to be taken in being oppressed, nor is there triumph in fighting for self-respect when dignity is God-Given--“Assuredly, We have honored the Children of Adam” (Surah al-Isrā’, The Night Journey, 17: 70). However, it is in fact Sunnah to heal the wounded and proclaim the favor of God upon those despised on account of their black skin or prior condition of servitude. Did not the Prophet صلى الله عليه وسلم command Bilāl to ascend the Kaaba and lift his voice and sing in full view of those who had once considered him a piece of property? Time alone will not heal the wounds of Black people, and so we call upon the Creator of time; praying for providence as we seek restoration. For Black communities in the Americas, reimagining ourselves has always incorporated influences home-grown and transatlantic, secular and religious, historical and futuristic. For our part, this book highlights the unrivaled redemptive power of Prophetic Islam. It establishes a conceptual basis for esteeming Africanity and brings forth from of our history exemplars of the noblest character. Imam Muhammad’s lucid and intuitive translation opens a vast window into Imam Suyūṭī’s beautifully written love letter to the people of the African continent. Imam Suyūṭī’s exploration of the Qur’anic terms that have Ethiopic roots enlightens us. His vignettes about the legendary wisdom of Luqmān and Umm Ayman’s love for the Prophet صلى الله عليه وسلم inspires us. However, I must submit that more endearing to me than all of the erudition of Imam Muhammad Mendes, which is on clear display in the original text, is his perceptive rendition. For nearly the last twenty-five years, American Sunni Muslim communities have struggled to substantively invest in our shared Black heritage. This failing can be traced back to two major lacunae, and Imam Muhammad’s selection of this work signals to me that he is intimately familiar with these gaps in our communal efforts. First, we have failed to invest in the history of our forbearers who were brought to this land in bondage. In Servants of Allah, Sylviane Diouf’s classic survey, the French-Senegalese historian places the proportion of Muslims among the enslaved community at roughly 30%. We have yet to effectively claim the legacy of the likes of Ibrahim Abd al-Rahman, Bilali Mohammed, Job Ben Solomon, Lamine Kebe, Omar ibn Said, and many other African Muslims instrumental in building and defining antebellum America. It is true that the African Muslims featured in Imam Suyūṭī’s text hail from a different time and region; East African Muslims feature prominently in the history of early Islam, while West African Muslims feature prominently in the history of America. Nevertheless, there is a conceptual tie that binds them. The brilliance of a work like Rafʿu Sha’n Al-Ḥubshān (The Spirits of Black Folk) is that it obviates the need to talk about any “Black contribution to Islam.” Black people never made a “contribution” to Islam. On the contrary, Islam has always been, in part, Black. Similarly, we appear undignified and crassly in need of validation when we speak of a Black or Muslim contribution to America. On the other hand, when we acknowledge that America has always been, in part, Muslim and Black, we are simply claiming our inheritance. From a posture of “principled belonging” as opposed to one of “aspiring to be accepted”, our cultural and political engagement with this culture can serve as more than a litmus test of our Americanness. This translation boldly exemplifies that spirit. Second, coming to terms with the unique history of Black American Islam has been challenging for our community. “The Second Resurrection” is a term coined by the great Imam Warith Deen Mohammed (God bless his soul) to describe the transition of Black Americans from earlier syncretic expressions of Islam (Moorish Science Temple of America (MSTA), Nation of Islam (NOI), and so on) into “orthodox” or Sunni Islam. “The Third Resurrection”, on the other hand, is a coinage of Dr. Sherman Jackson, and describes the process by which “Blackamerican Muslims” seek to gain mastery over the Islamic intellectual tradition and to apply it in relevant and effective ways. A thorough treatment of this history lies beyond this foreword. However, in the interest of spotlighting the timeliness of this beautiful work, I would like to focus on two closely related factors within these Resurrections, namely, our struggle to understand the advantage (yes, advantage) of syncretic religion, and our struggle to induce the institutions, traditions, and texts of historical Islam to speak our language. Opposition to religious syncretism (bidʿa) is a core tenet of Sunni Islam. When you add to this the fact that denunciation of the NOI became a sixth pillar of Islam among Blackamericans, the result is a form of communal amnesia. Personally, I find great satisfaction in the theology of Sunni Islam. There is something indescribably authentic about entering a trans-historical and intercultural conversation about God. However, when our enthusiasm leads us to throw out the proverbial baby with the bathwater, we do ourselves a great disservice. The NOI was largely responsible for indigenizing Islam among Blackamericans. We have not fully appreciated this unprecedented feat. We should be more interested in discerning what it was about the character of that movement that contributed to its enthusiastic reception. Among many other factors, the NOI benefitted from the malleability and responsiveness of syncretic religion. In other words, free of the task of negotiating religious thought and practice developed in other contexts, the NOI never had to sacrifice relevance for authenticity. As our nation—and by extension our community—continues to deliberate, holds rallies, and accepts accountability concerning the value (or lack thereof) we have assigned to Black life, Imam Muhammad’s translation could not be more relevant. With this work, he has done more than merely show that tradition is not an impediment to relevance. By choosing a book authored by one of the greatest scholars in Islamic history and translating it with considerable skill and elegance, he has shown that tradition can not only respond to contemporary challenges, but, indeed, expand our understanding of them. Personally, I am excited about this book. I think it represents visionary thinking on behalf of many: CelebrateMercy, Tarek El-Messidi, the Imam Ghazali Institute, and all of the wonderful students who attended the initial Black Lives around the Messenger صلى الله عليه وسلم course whose engagement led to this project. As an American Muslim community, our collective sense of mission is framed by the objectives of our Sacred Law: to preserve faith, life, intellect, family, wealth, and dignity. This is the promise of Islam to humanity. The Prophetic Way instructs us to begin by restoring those essentials to those from whom they have been taken. In the case of Blackamericans, the imperative is clear. Imam Adeyinka Muhammad Mendes, I thank you and I commend you for getting us back on mission. Ubaydullah Evans 1 Jumādā al-Ākhirah 1442 Please click here if you would like to purchase, The Spirits of Black Folk: Sages Through the Ages

https://store.celebratemercy.com/discount/ALIM5 Comments are closed.

|

|

stay connected

@alimprogram

PO Box 871785 Canton, MI 48187

(734) 956-0698

(734) 956-0698

2024 © American Learning Institute for Muslims. All rights reserved.

ALIM is a 501(c)(3) organization. All donations are zakat-eligible and tax deductible. Our EIN is 38-3633579.

Zelle: [email protected]

Terms of Service | Privacy Guidelines | Sign Up for ALIM Emails I Get ALIM Text Alerts

ALIM is a 501(c)(3) organization. All donations are zakat-eligible and tax deductible. Our EIN is 38-3633579.

Zelle: [email protected]

Terms of Service | Privacy Guidelines | Sign Up for ALIM Emails I Get ALIM Text Alerts

RSS Feed

RSS Feed