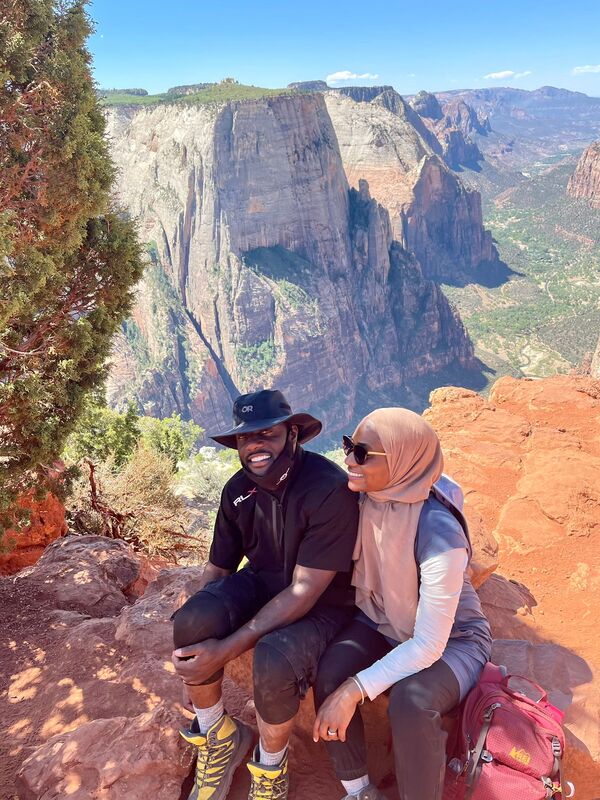

Ustadh Ubaydullah EvansMy friends, Imam Dawood Yasin and Imran Malik named the Clubhouse room “Evergreen Soul.” I had recently returned from a family hiking trip in Utah—for which Imam Dawood graciously assisted me with my equipment—and I agreed to share some stories. This trip, organized by my wife Hadiyah and with her careful, meticulous planning, was a first for our family. I entered the room prepared to offer standard fare: Funny anecdotes about my children and the stale bon mot about the gaping mouths and curious glances generated by a Black, Muslim family in rural Utah. What I encountered, however, was a deeply impassioned conversation led by two erudite Muslims who were also experienced outdoorsmen. The spiritual and intellectual vistas that were explored during the session—by the hosts as well as the attendees—prompted a reflection. It’s really quite odd. The Qur’an is replete with verses that exhort humanity to gaze contemplatively upon the world. The following verse of Sūrat al-Mulk is a personal favorite: “He is the One ‘Who created seven heavens, one above the other. You will never see any imperfection in the creation of the Most Compassionate. So look again: Do you see any flaws? (3) Then look again and again—your sight will return frustrated and weary. (4) [67: 3-4] In fact, the Qur’ānic Revelation assumes us to have an intentional relationship with the flora and fauna of the natural environment. If not, the verses encouraging devotion through contemplating creation would be unintelligible. And yet, I’ve always felt a certain aversion to being “outdoorsy.” For me, it evokes “bobo” imagery. The designation “bobo” was introduced by conservative political commentator David Brooks in his book, “Bobos in Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There.” The term, which is a portmanteau for “bourgeois bohemians,” is used to describe a fusion between two distinct social classes: the white collar, capitalist bourgeois and the counter-cultural, hedonistic, and artistic bohemian. For reasons I’ve yet to adequately explore, “outdoorsy” culture coming onto my radar with this particular genealogy always left me feeling slightly ambivalent.

Nonetheless, I claim no special authenticity for myself. We all consciously and subconsciously participate in social rituals that announce our class affiliations. Today’s “bobo” is simply yesterday’s “yuppie” or in my specific case, “buppie” (Black urban professional). However, in addition to being as potentially contrived and commercially driven as yuppie, hipster, or foodie culture, the category “outdoorsy” at times appears to carry a repulsive self-righteousness. The preachy, environmentally-conscious, anti-capitalist minimalist who spends thousands of dollars on gear at REI to go “off the grid” is the stuff of sketch-show comedic gold! And yet, if the space within my heart that should be occupied by a desire to commune with the creation of God is instead filled with derisive mocking of “glamping,” who’s more deserving of the label “superficial?” Imam Dawood spoke of intentional engagement with nature in a register too profound to be referred to as “outdoorsy.” He wasn’t referencing a pedestrian fascination with being outside of doors or even an urge to make an occasional spiritual pilgrimage to the wilderness for the purpose of interrupting our soul-crushing, mechanized, artificial daily routines. Rather, he spoke of being in regular contact with nature as a source of achieving balance, equilibrium, and most importantly guidance. While sharing an insight of a young woman who participated in an outdoor activity which he led, the Imam mentioned that to enter a natural environment is to enter a place that is without sin, a place in perfect harmony with the Will of God. Viewed against such a grand backdrop, the weightiness of the deputation God has entrusted to men and women—by making us free-choosing, accountable beings—is drawn into sharp relief. “We did indeed offer the Trust to the heavens and the Earth and the Mountains; but they refused to undertake it, being afraid thereof: but the human being undertook it; He was indeed unjust and foolish.” [33:72]. Human willingness to undertake the “Trust,” which was initially refused by the natural world, is the thing which qualifies us as the vicegerents of God and thus the potential objects of His love. When we choose submission (Islam) to God, He loves that we have chosen to submit to Him. However, those elements of God’s creation granted no right to choose exude no less the peace, beauty, tranquility, and harmony that results from being in submission to God. Whenever, I reflect upon the time our family spent touring the rugged, mountainous canyon lands of Utah, two things occur to me: The first is that the United States of America is a country of breathtaking geological and topographical diversity. The history of this nation represents a whirling vortex. The grave crimes of racial slavery and genocide intersect with the irrepressible humanity expressed in America’s continued quest for social justice and civil rights. And yet the beauty and generosity of the land itself has remained a constant. Secondly, I reflect on the words of the twentieth-century Anglo-American poet, W.H. Auden who wrote. Looking up at the stars, I know quite well That for all they care, I can go to Hell But on Earth indifference is the least We have to dread from man or beast. How should we like it were the stars to burn With a passion for us we could not return? If equal affection cannot be Let the more loving one be me… In these lines, Auden recognizes that the passion he feels for the stars cannot be reciprocated. But he also recognizes that in being the “more loving one” he is satisfied. Ubaydullah Evans Chicago 2021

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

|

stay connected

@alimprogram

PO Box 871785 Canton, MI 48187

(734) 956-0698

(734) 956-0698

2024 © American Learning Institute for Muslims. All rights reserved.

ALIM is a 501(c)(3) organization. All donations are zakat-eligible and tax deductible. Our EIN is 38-3633579.

Zelle: [email protected]

Terms of Service | Privacy Guidelines | Sign Up for ALIM Emails I Get ALIM Text Alerts

ALIM is a 501(c)(3) organization. All donations are zakat-eligible and tax deductible. Our EIN is 38-3633579.

Zelle: [email protected]

Terms of Service | Privacy Guidelines | Sign Up for ALIM Emails I Get ALIM Text Alerts

RSS Feed

RSS Feed