By: Dr. Sherman A. JacksonALIM Core Scholar I have no problem condemning the killing of innocent civilians, wherever and whoever they might be. This is among the dictates of the Qur’ān itself. “O you who believe, be upholders of justice, witnesses for God, even if against yourselves.”

Once, the Prophet (SAWS) sent a group of Companions on a reconnaissance mission and gave them explicit instructions to do nothing but gather intelligence. They saw a Qurayshi caravan, however, and decided to attack it. Quraysh was outraged and set out to scandalize the Prophet, as this attack took place in one of the Forbidden Months, which banned anyone from attacking anyone. The Qur’ān refers to this incident in Sūrat al-Baqarah, 2: 217: “They ask you about fighting in the Forbidden Months. Say, fighting in them is an abomination. But impeding the path to God and rejecting Him, as well as the Sacred House, and turning its people out is an even greater abomination. And subjugation is worse than killing (wa ‘l-fitnatu akbar min al-qatl).”

3 Comments

When the Prophet Muhammad moved from Mecca to Medina, he declared that the Muslims and the rest of the inhabitants of his new home constituted an ummah. This is explicitly, not implicitly, laid out in the so-called Constitution or Ṣaḥīfah of Medina. I want to declare, as did the Prophet in his own time and circumstances, that the Muslims and the rest of the inhabitants of America constitute an ummah, a single political community defined by mutual rights and mutual responsibilities.

The Election of Donald Trump: A Referendum on Liberalism? By Dr. Sherman Jackson I am not a political conservative, at least not in the American tradition of that brand.[1] First, conservatives tend to be “no-men” who merely act as brakes on liberal progress, with no life-enhancing vision of their own. Second, conservatives tend to recognize no distinction between moral and political judgments; to be morally or religiously opposed to drinking alcohol, e.g., means to have to ban it for everyone as a matter of law. Third, conservatives tend to reflect the same conceit they decry in liberals: the ability to speak for everyone through the false universalization of their own historically or culturally informed perspectives. Fourth, conservatives tend to sanctify personal wealth in the same way that liberals sanctify personal rights. Finally, there is something in the American past that conservatives seem to want to conserve that I find it difficult to disentangle from white supremacy.

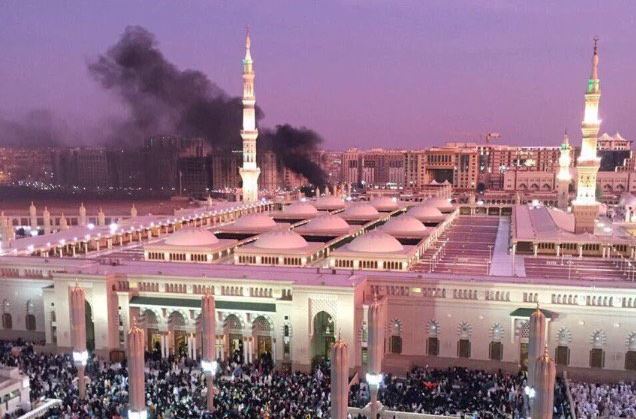

And Now Medina: Beyond the Elephant’s Shadow By Sherman A. Jackson I do not know the specific grievance that drove the suicide bomber to his despicable deed in our beloved Medina, Islam’s second holiest city. I suspect, however, that it had something to do with some perceived decline in public adherence to Islam. Or perhaps it was the feeling that the government was not living up to the standards of Islamic justice. Whatever the motivation, this suicide bomber was somehow convinced that his action was ‘Islamic’. Indeed, I doubt that he saw himself as purchasing some one-way ticket to hell. Of course, his action will ultimately prove totally ineffective in addressing whatever grievance he had in mind. And this is the ultimate tragedy of the situation, which raises a number of questions: Why do Muslims resort to this kind of violence when it has such a little chance of producing the change they want? Why is it so seemingly easy to convince them of the legitimacy of such violence in the name of Islam? And why are Muslim condemnations of this mentality and the vile deeds that accompany it seemingly so ineffective?

After Ali: The American Muslim Community Between Principle And Interest By: Sherman A. Jackson The funeral and memorial service of our beloved champion Muhammad Ali have inspired the American Muslim community and spawned a new sense of possibility. The explicit and heartfelt national recognition of Ali’s legacy as an American Muslim has provided Muslims in this country, of all walks and all backgrounds, with a new mandate of sorts to build and perhaps reimagine their future as a community thoroughly at home in its sense of being Muslim, thoroughly at home in its feeling of being American and thoroughly recognized as unapologetically both by America and the world.

The Austro-American Sociologist of Religion, Peter Berger, is noted for coining the term and concept of “plausibility structure.” Basically, a plausibility structure is the overall sociocultural context within which a system of meaning, an institution or a set of beliefs acquires its status as “real,” “valuable,” “normal” or even “true”. Individuals who live in this sociocultural context are not likely to defy or flout these beliefs or institutions but to acquiesce to them, take them for granted and ultimately assimilate them as their own. This does not mean that every individual is a dedicated champion of the reigning beliefs, meanings or institutions. But the prevailing plausibility structure will contribute to one’s sense of identity, morality and reasonableness; and it will impose both a psychological and a social cost on going against established norms. No American president, for example, regardless of his or her own actual beliefs, could proclaim a commitment to racial segregation, unequal pay for women or even atheism. And few American Muslims, again, regardless of their true understandings or commitments, would challenge the reigning paradigms of “human rights,” “free speech” or “separation between religion and state”.

Many if not most people tend to equate denial of freedom with criminalization backed up by the possibility of jail. In reality, however, there are many other ways to restrict a person’s freedom. Generally speaking, if the price of exercising a particular freedom can be made high enough, people will simply ignore or consciously forfeit its gradual loss. This price can be in terms of money, loss of reputation, or fear of being ostracized, brought under suspicion or associated with unpopular groups, individuals, ideologies or agendas. The recent Supreme Court decision, for example, Citizens United vs. the Federal Election Committee, granted corporations the right to make campaign contributions. While it directly imposed no restrictions on the freedom of non-corporations, it clearly reduced the ability of individuals to protect and promote their rights and interests relative to those of the super-rich. Yet, the disparity in money and influence between the average person and large corporations is so massive that most people will simply ignore the impact of this decision on the meaningful exercise and eventual erosion of their political rights and freedoms.

The Gift of Historical Consciousness

I have often wondered about the way Muslims use the word “ummah.” In a technical sense, it clearly refers to the entire Community, the unqualified collective of all who espouse, “There is no god but God and Muhammad is His messenger.” And yet, it commonly manages to connote certain parts of the world to the marginalization if not mild exclusion of others. The Middle East, South Asia and South East Asia clearly make it in, while America, Canada and Jamaica are barely brought to mind. Ultimately, of course, numbers play a role here. Where Muslims are a majority or even a ‘significant minority’ (as, e.g., in India or parts of Africa), it is simply easier to see their sufferings, obsessions, preferences and even sensibilities as reflecting the pulse and interests of the “ummah.” Where they are a small, marginal minority, on the other hand, (as, e.g., in America or Canada) this is far less likely to be the case. NOTE: The following is a mildly edited transcript of the keynote address given by Dr. Jackson at the Annual Community Dinner of the Council of Islamic Organizations of Greater Chicago held on October 15, 2011 in Rosemont, Illinois. It has been slightly edited for brevity and clarity.

A most insidious impediment to a dignified existence for Muslims in America is the basic misunderstanding of the truism that Islam and secularism are mutually exclusive. Inasmuch as America is a “secular democracy,” many non-Muslims insist that no religion that positions itself as the polar opposite of the secular should be allowed to play a meaningful role in determining the country’s direction. In fact, in their view, allowing Muslims to influence public debate risks undermining the country’s secular order. Meanwhile, many Muslims quietly share aspects of this perspective, even if for practical reasons they come to a different set of conclusions. They too see an inherent contradiction between Islam and the secular, as a result of which they view participation in American public life almost as a necessary evil, to be indulged only out of a sense of duress, sort of like eating swine to ward off starvation.

By Dr. Sherman Jackson

(Published in Ascent Magazine Vol 2. Issue 1&2) I. INTRODUCTION “Islam is a religion of peace.” This is certainly the mantra that has inundated us from almost every quarter since the horrifying events of September 11, 2001. From President George W. Bush to local, national and even international Muslim spokespersons, the peaceful nature of Islam has been reiterated time and again. Of course, this has not gone unchallenged. Skeptics, polemicists, even opportunists of various stripes, have repeatedly warned against accepting too uncritically what they hint at being a “new-found, politically correct” depiction of a religion that includes, inter alia, a scripturally mandated institution of armed violence and a holy book that exhorts its adherents, at least on the face of it, to “slay ‘them’ wherever you find them.”[1] Today, close to a year after the tragedy, emotions and rhetoric on both sides have subsided a bit. But there is still a suspicion among many Americans-including many Muslim Americans-when it comes to the question of Islam, violence, and the relationship between Muslims and non-Muslims. The passing of Imam W.D. Mohammed, may God have mercy upon him and grant him Paradise, has brought the Blackamerican Muslim community face to face with a reality that it has been more comfortable with ignoring than coming to terms with. Imam Mohammed’s death has signaled the end of the era of charismatic leadership in which the rank and file can look to a single leader to settle all major questions and chart the Community’s course for the future. Rather than being decided by a single voice, that future will have to be negotiated by the collective understandings and perspectives of the Community’s learned. This implies, of course, general agreement on who is learned and what the rules of engagement are. If the criterion is set too high, it will marginalize valuable voices and confirm an already widespread distrust of religious knowledge and those who claim to represent it. If it is set too low, it will open the Community to the ravages and abuses of those who think that the role of religion is to sanction their and or the dominant culture’s every undisciplined whim and passion.

In the years leading up to his death, Imam Mohammed strove mightily and with great farsightedness to empower his Community to carve out a dignified existence for themselves, to transition to what I have referred to as the “Third Resurrection,” whereby, individually and collectively, the Community is able to negotiate American reality in light of the Qur’an and Sunna. For the most part, however, the Imam had to go it alone, with few contributions from Blackamerican Muslim scholars outside his own movement. |

|

stay connected

@alimprogram

PO Box 871785 Canton, MI 48187

(734) 956-0698

(734) 956-0698

2024 © American Learning Institute for Muslims. All rights reserved.

ALIM is a 501(c)(3) organization. All donations are zakat-eligible and tax deductible. Our EIN is 38-3633579.

Zelle: [email protected]

Terms of Service | Privacy Guidelines | Sign Up for ALIM Emails I Get ALIM Text Alerts

ALIM is a 501(c)(3) organization. All donations are zakat-eligible and tax deductible. Our EIN is 38-3633579.

Zelle: [email protected]

Terms of Service | Privacy Guidelines | Sign Up for ALIM Emails I Get ALIM Text Alerts

RSS Feed

RSS Feed