|

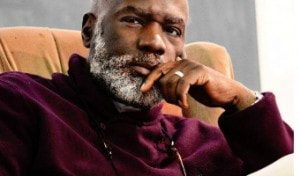

After Ali: The American Muslim Community Between Principle And Interest By: Sherman A. Jackson The funeral and memorial service of our beloved champion Muhammad Ali have inspired the American Muslim community and spawned a new sense of possibility. The explicit and heartfelt national recognition of Ali’s legacy as an American Muslim has provided Muslims in this country, of all walks and all backgrounds, with a new mandate of sorts to build and perhaps reimagine their future as a community thoroughly at home in its sense of being Muslim, thoroughly at home in its feeling of being American and thoroughly recognized as unapologetically both by America and the world. Yet, there is a danger, I fear, of the meaning and importance of Ali being sacrificed to an understandable desire (given the fragility of the socio-political moment in which we live) to instrumentalize his legacy in ways that misapprehend and thus betray his commitment to principle, in pursuit of an endless series of unstable, mutually contradictory short-term interests. Of course, Ali lived a long, event-filled life, harnessed sizeable resources, faced many challenges and dedicated himself to numerous causes. Few of us have the time, wherewithal or inclination to extend ourselves as broadly as he did. Thus, as a simple matter of our limitations as individuals, some of our commitments will overlap with his, while some will not. This alone, however, should not be taken as a justification to indict people on charges of hypocrisy simply because, in invoking the memory of Ali, they identify with some of the causes he championed while seemingly ignoring or down-playing others. Nobody can do everything; nobody. It is important, however, to recognize that Ali’s life was underwritten by an overall commitment to principle. In fact, it was his addiction to principle that earned him the ire of his adversaries, the love of those whose cause he championed and, ultimately, the respect and admiration of both. Ali’s primary commitment was not to “serving people,” as some seem to think; nor was that the reason he eventually won his adversaries over. Ali’s primary commitment was, rather, to serving God, as he understood God, as a matter of principle and because he believed he had a non-negotiable obligation to do so. The people he served were simply the beneficiaries of this non-negotiable commitment, in the same way the Qur’ān portrays the poor, orphans and prisoners of war benefiting from Muslims’ commitment to God: “We feed you purely for the sake of God. We desire from you neither reward nor thanks.” [76:8] As for Ali’s adversaries, they ended up evolving in a manner that reflects the lesson the Prophet’s wife ‘Ā’ishah shared with the Companion and first Umayyad Caliph, Mu‘āwīyah b. Abī Sufyān: “Whoever seeks the pleasure of the people via actions that are displeasing to God, God will cause His and the people’s displeasure to descend upon them. But whoever seeks the pleasure of God, even if at the displeasure of the people, God will eventually cause both His and the people’s pleasure to descend upon them.” This quintessentially religious calculus is often the first thing to go in our attempt to negotiate a world seemingly aligned against us. And yet, this commitment to principle was the very core of Ali’s approach and the reason he acquired the one thing without which we would not be celebrating his legacy today: credibility. When Ali spoke (outside the ring), it was not merely for public consumption; nor was he seen as simply telling people what they wanted to hear. By contrast, the biggest and most dangerous liability facing the American Muslim community today is their lack of credibility. On the one hand, the words and deeds of actors in the “Muslim world” are taken to be far more representative of “true Islam” than the ideals, apologia and even accomplishments of American Muslims themselves. Even their misdeeds are routinely identified as an extension of some radical, overseas ideology rather than being accepted as a reflection of plain old human frailty or homegrown American malaise. On the other hand, rather than take a principled stand that recognizes that those who do not believe in their religion (or revealed truth at all, for that matter) may simply not agree with certain aspects of Islam, the American Muslim reflex tends to be towards the attempt to craft some universally acceptable version of the religion. This may buy time; and it may entertain. But it is not likely to translate into credibility. For, the American suspicion of religion – all religion! —which it inherited from its European past, invariably generates a nonstop search for just enough hypocrisy or buzzkill in religious people to justify the domestication of religion. This ultimately translates into a litmus test that no religion peopled by real human beings could possibly meet. And in our attempt to satisfy this impossible criterion, by emptying Islam of anything that might offend any sensibility, we end up looking like, as Ibn Qudāmah famously put it, “the blind man who answers the call of nature facing a crowd of people, thinking that they can’t see him simply because he can’t see himself.” Ali’s legacy was, to my mind, that of the tragic hero. The tragic hero knows that commitment to principle is neither perfected overnight nor always productive of immediate gain. Commitment to principle is hard and costly. And the tragic hero is fine with that. For, s/he sees victory not solely in vanquishing the enemy but more importantly in strengthening and preserving his or her own principles. The tragic hero is not always optimistic; for s/he is too honest for that. But s/he is always hopeful; for s/he believes in an ultimate justice beyond this world. This is why s/he is courageous and able to sacrifice, forgive, suffer and persevere. And this is why s/he is humble enough to accept yet struggle against his or her flaws and shortcomings, instead of always having to try to validate these or pretend that they don’t exist. Because of all of this, the tragic hero is able to earn the people’s trust. And trust is the critical element in any successful human relationship. American Muslims, I think, may want to consider carefully whether they want to invest all of their energies in the short-term interest of “better press,” broader acceptance or a self-referential moral infallibility, or commit themselves long-term to living out their principles, warts and all, in a manner that earns America’s trust, as Ali did. But there is another aspect to all of this that must be grasped if we are to preserve the legacy of Muhammad Ali. Ali’s success cannot be separated from his relationship with the broader Blackamerican community. It was they who embraced him as one of their own and made it clear that an assault on him was an assault on their collective dignity. It is naive to think that Ali’s case would have made it all the way to the Supreme Court without the pressure and concern generated by the broader Blackamerican community (and some others). In short, Ali did not do it all by himself. Rather, the Blackamerican community functioned in effect as his Banū Hāshim. Just as the Prophet’s pagan clansmen came to his defense and put their livelihoods and reputations on the line, the Blackamerican community did the same in the case of Ali. Numerous Blackamerican celebrities, from Bill Russell to Jim Brown to Sammy Davis, Jr. (a Jew!) put their reputations and possibly careers on the line by coming to the defense of one of the most controversial figures of his time. This they could do, however, because they had a clear sense that the commitment was reciprocal: Ali would have done the same for any of them. Here’s where the American Muslim community must gain some clarity regarding the relationship between its principles and its interests. Personally, I believe that the future of Islam in America is intimately tied to the ability to restore the religion to the place of honor, respect and positive anticipation it once enjoyed in the Blackamerican collective psyche. This has nothing do to with any biological, race-based theories of inherent superiority. But the Blackamerican community in America is Islam’s indigenizing agent. And just as the Prophet’s success in Arabia hinged on his relationship with his clan of Banū Hāshim, so too will that of Muslims in America on their relationship with the broader Blackamerican community, not simply in socio-political terms but also in terms of their ability to fashion a culture in America that is strong, attractive, indigenous, open and efficacious enough to sustain the values, virtues and moral identity of Islam. And here is where we come to the question of principle versus interest. For the broader Blackamerican community will only be willing to function as the Muslim community’s Banū Hāshim to the extent that they can trust the latter to reciprocate, in good times and in bad. This means that the Muslim community will have to demonstrate a principled rather than a purely self-serving or a self-defeating approach to pursuing its legitimate interests. And this implies at least two truths: 1) the burdens of political alliances must be fully recognized and willfully born; 2) a political alliance that ultimately renders one less rather than more (or at least equally) capable of sustaining one’s own principles is itself neither sustainable nor reliable. In the all-too-understandable interest of appealing to and staving off the critique of the dominant culture, mainstream Muslim organizations and leadership have been willing largely to ignore the Blackamerican community. Indeed, they seem to assume that by identifying with such individuals as Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali they pay sufficient homage to the legacy of Blackamericans, and in so doing qualify for the benefits that go along with this would-be gesture of recognition. In reality, however, the legacy of these Blackamerican heroes is part of the history of Blackamericans as a whole. And only a genuine, i.e., principled – as opposed to a token – identification with that history will generate the kind of trust and mutual consideration that can establish a truly synergistic relationship between the Muslim and broader Blackamerican communities. This includes a willingness on the part of American Muslims to sacrifice, suffer, pick sides and take perspectives that transcend the psychological boundaries within which they have grown accustomed to operating. Of course, commitment to principle also means that Muslims will not simply check their Islamic moral identity at the door when engaging the Blackamerican community or its issues. But the principles undergirding this moral identity must be engaged in a manner that render them at least as malleable and accommodating in the face of Blackamerican specificity as they are in the face of the specificities of peoples in the traditional Muslim world. This is the challenge to which we must now rise, especially in the post-Ali era. Otherwise, I fear that Ali’s legacy, like that of Malcolm before him, will gradually fade into a fashionable yet hollow memory that does little work on the ground beyond ultimately reminding us, at some distant point in the future, of just how blinded we were by fear, self-loathing, prejudice, the thirst for validation, short term interests and the desire to avoid confrontation. By then, however, it may simply be too late. And we, or more properly our progeny, may be left to pay a price that is higher than we or they can afford to pay. Alas, bi’rin mu‘aṭṭalatin wa qaṣrin mashīd. [22:45][1] And Allah knows best.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|

stay connected

@alimprogram

PO Box 871785 Canton, MI 48187

(734) 956-0698

(734) 956-0698

2024 © American Learning Institute for Muslims. All rights reserved.

ALIM is a 501(c)(3) organization. All donations are zakat-eligible and tax deductible. Our EIN is 38-3633579.

Zelle: [email protected]

Terms of Service | Privacy Guidelines | Sign Up for ALIM Emails I Get ALIM Text Alerts

ALIM is a 501(c)(3) organization. All donations are zakat-eligible and tax deductible. Our EIN is 38-3633579.

Zelle: [email protected]

Terms of Service | Privacy Guidelines | Sign Up for ALIM Emails I Get ALIM Text Alerts

RSS Feed

RSS Feed