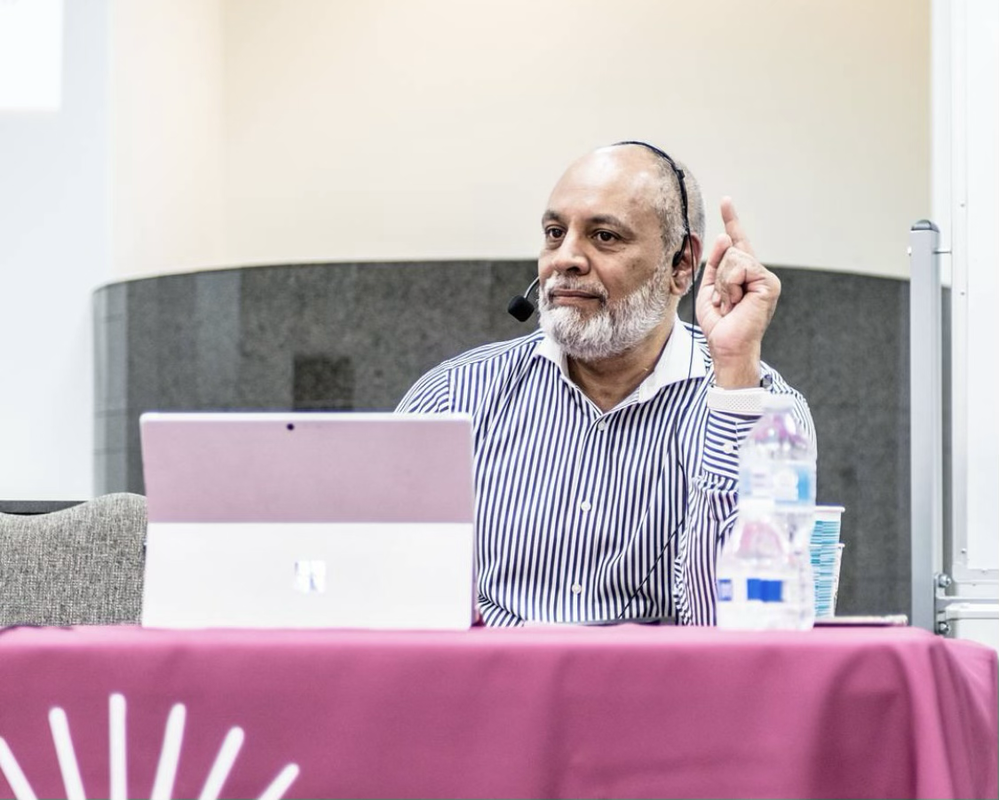

by: Dr. Muneer FareedALIM Core Scholar Where are the Leaders! This latest attack on Ghazza raises difficult questions pertaining to leadership, and brings into sharp relief, once again, the tension between the leaders we demand and those we deserve. We demand of our leaders that they speak truth to power, when in fact, we should try and limit our demands to that which plays to their strengths, bearing in mind that strengths vary from person to person. Unfortunately, some of our leaders are equally to blame: instead of trying to punch above their weight they too should limit themselves to their strengths, and work on curbing their urge to bask in the limelight. And since this is also turning out to be an attack on our civil liberties, we should be concerned about the costs leaders incur in speaking out. The threats now being leveled against them for supporting human rights in Palestine could well be deployed later to further curb other rights we take for granted. After all, not too long ago, the ‘war on terror’ was used as a pretext for the state to take control of what goes where. Which leaves one wondering whether constitutional rights extend fully to all of us, or only to the chosen few willing to stick their necks out for causes approved by the establishment?

Rest assured, such concerns plague Muslims not just here in the United States but also in some less obvious regions of the world. The Middle East clearly is where mere silence is not an option, where nothing short of a full rebuttal of Hamas, or the Houthis, or Iran, or conversely, Saudi Arabia, gets the mukhabarat off your back. And this apparently applies even to those caught in the cross hairs of Israel’s very own hysteria. The Times of Israel recently ran a piece questioning the loyalty of the local imams to the state of Israel. It asks why these imams (citizens of Israel) are silent in the face of terrorism which harms and desecrates “the image of God in our world.” As evidence it cites an interfaith prayer vigil held in Tel Aviv in solidarity with families of the hostages, attended by religious leaders from the Jewish, Druze, and Christian communities, but not a single Muslim. It laments the fact that no imam “would agree to join our joint call against the criminal terrorism of Hamas against innocent citizens and for the immediate, unconditional return of the hostages to their families, even though that is what we are commanded to do and how Allah would conduct himself in this world.” Meanwhile, I’m almost certain Muslim Israelis also want more of their imams than just their deafening silence. Right next door, in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt, the Madkhalis and the Sahwis cross swords again, in defense of their favorite dictator, or in promoting some ill-conceived revolution. And then there are some local leaders who over the years have grown more beholden to Khaliji and Saudi handouts, and who seem just as hard-pressed to say what’s right. Let’s not forget, taking on the establishment is always what separates the moral wheat from chaff, and only a handful have what it takes to step into the shoes of an Ahmad ibn Hanbal, or Edward Said, rather than, say, Fuad Ajami. Ibn Hanbal, as is well known to students of history, was the lone holdout during the Mihna, or that period of intense religious persecution which forced his colleagues to bend to the will of the ruling elite. It is also from Ahmed’s experience we learn that not every expert in tafsir or tasawwuf is gutsy enough to take the moral high ground, and that as disciples, or congregants, or students, we should therefore, lower our expectations, and ask not of them to carry too big a burden. To take academics as an example, how should they respond to global events outside their ecosystem? Should they adopt the position of academic-activists or continue to remain neutral in keeping with the demands of their professions? Adopting the hybrid approach, critics point out, eventually erodes public trust in the objectivity of academic research itself. This applies not just to the situation in Palestine, but also to race relations, gender justice, or the war in Ukraine. Unlike the activist, the academic is expected to pursue his craft with fairmindedness, humility, and a commitment to unraveling the truth. But this is particularly difficult for those among us who actually turned to academia to find solutions to the injustices we witnessed in the trenches. The initial plan was to analyze such injustices, and then offer some solutions in the public square. But the subtle pressures of the establishments to which we belong, not to mention the concerns we all have for job security and career development, make any attempt to go public gut wrenching. And the same applies to all our leaders, whilst most are quite competent in offering conventional wisdom, most are not up to the task of doing so under unconventional circumstances.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|

stay connected

@alimprogram

PO Box 871785 Canton, MI 48187

(734) 956-0698

(734) 956-0698

2024 © American Learning Institute for Muslims. All rights reserved.

ALIM is a 501(c)(3) organization. All donations are zakat-eligible and tax deductible. Our EIN is 38-3633579.

Zelle: [email protected]

Terms of Service | Privacy Guidelines | Sign Up for ALIM Emails I Get ALIM Text Alerts

ALIM is a 501(c)(3) organization. All donations are zakat-eligible and tax deductible. Our EIN is 38-3633579.

Zelle: [email protected]

Terms of Service | Privacy Guidelines | Sign Up for ALIM Emails I Get ALIM Text Alerts

RSS Feed

RSS Feed