By Ustadh Ubaydullah evansPhotograph by Stephanie Strasburg / Pittsburgh Post-Gazette AP Why did one straw break the camel’s back? / Here’s the secret/ the million other straws underneath it/ it’s all mathematics —Yasiin Bey (Mos Def).

Islamic law predates the creation of the modern nation-state. As such, the kind of legal monism (idea of there being a single “law of the land”) and centralization of power enjoyed by modern nations was unfathomable to Muslim political theorists in the classical period. By comparison, theirs was an ethic of non-domination and personal liberty vis-à-vis the State—at least with regard to a matter like the right to bear arms. Interestingly enough, it appears that this incidental feature of the pre-modern world (non-domination vis-à-vis the State) is an intentional moral commitment for those who refuse to countenance any nullification of their 2nd Amendment rights. However, our tradition subjects all moral commitments to an assessment of their impact on the Maqāṣid (objectives) of the Shari’ah. The preservation of: Faith, life, family, human cognitive ability, wealth, and dignity. Stated differently, where the will of God is concerned, no moral commitment that can be shown to harm or jeopardize the aforementioned values can be regarded as sound.

0 Comments

By Ustadh ubaydullah evans“I was once riding behind the Prophet (upon him be peace) and I recited to him one hundred couplets from the poetry of Umayyah ibn Abī aṣ-Ṣalt al-Thaqafī. Each time I recited a couplet, the Prophet (upon him be peace) would say to me, “Recite more!” until I recited one hundred couplets, whereupon the Prophet said, ‘He nearly embraced Islam.’”

By now, it appears the whole world knows that Will Smith assaulted Chris Rock during the live broadcast of the Oscars. And if it weren’t for one of the most strenuous branding campaigns in modern show business, the public might have taken the unfortunate incident at face value: Will Smith lost control over his emotions and unjustly slapped Chris Rock for an ill-conceived joke. However, in the process of building a multi-media empire, the Smiths have opened intimate and sometimes unsettling details about their personal lives. As a result, social commentary on the incident has framed Will Smith as everything from a vengeful cuckold trying to reassert his masculinity to a tutored soul, reliving the trauma of watching his mother suffer domestic violence. The carousel of public opinion continues to spin: biting, satirical, pseudo-therapeutic but very rarely introspective. For the Muslim community, I see two issues of interest here. First, should we even care about this? Does concern about what happened between Will Smith and Chris Rock represent an unjustifiable descent into the inane and vulgar? Secondly, as opposed to either aimless schadenfreude or psychological quackery, is there anything we can learn about ourselves and our tradition from this incident? Ustadh Ubadullah evansTa’ḍhīm ash-Shari’ah or esteem for the law has always defined the Muslim community. Familiarity with the language of the law and its categories among non-specialists is a unique feature of our community. If truth be told, as a student of Shari’ah, I express a quiet joy each time I encounter Muslims who negotiate the realities of day-to-day life through the use of terms like: ḥarām, halāl, makrūh, obligatory, permissible, recommended, etc. Whether we have training in Islamic law or not; deploy the language of the law with precision and clarity or not; simply invoking the law expresses some of our deepest moral commitments. Namely, that the God we serve is concerned about us and has given us guidelines by which to lead good lives. Additionally, a concern with law articulates a faith that is relevant in the lives of believers.

Ustadh Ubaydullah EvansALIF. LĀM. MĪM. The first verse of Sūrat al-Baqarah and perhaps one of the most well-known of the Qur’ān is simply three seemingly unrelated letters. The ḥurūf al-muqaṭṭa’āt, the disjoined letter combinations which begin twenty-nine separate chapters of the Qur’ān are considered a mystery by the vast majority of classical authorities. Although exegetical literature reveals much speculation about these letters, nothing definitive is offered in the Qur’ān nor attributed to the Prophet (upon him be peace). The subtle irony is that this scripture, which contains verses such as:

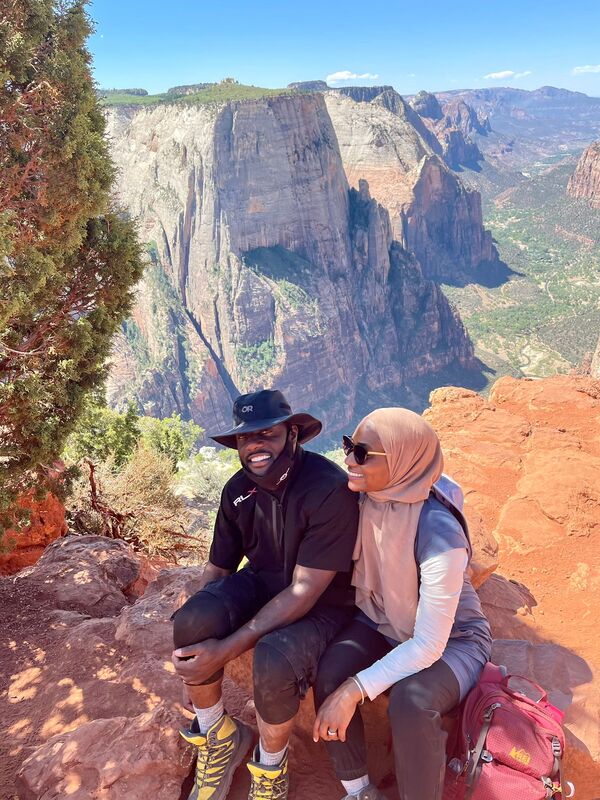

{“We have sent it down as an Arabic Qur’ān so you may understand.” Quran 12:2} {“And we have revealed the Book as an explanation of everything.” Qur’ān 16:89} {“Those to whom we have given the book (the Qur’ān) study it as it should be studied: they are the ones that believe therein: those who reject faith therein the loss is their own.” Quran 2:121} Ustadh Ubaydullah EvansMy friends, Imam Dawood Yasin and Imran Malik named the Clubhouse room “Evergreen Soul.” I had recently returned from a family hiking trip in Utah—for which Imam Dawood graciously assisted me with my equipment—and I agreed to share some stories. This trip, organized by my wife Hadiyah and with her careful, meticulous planning, was a first for our family. I entered the room prepared to offer standard fare: Funny anecdotes about my children and the stale bon mot about the gaping mouths and curious glances generated by a Black, Muslim family in rural Utah. What I encountered, however, was a deeply impassioned conversation led by two erudite Muslims who were also experienced outdoorsmen. The spiritual and intellectual vistas that were explored during the session—by the hosts as well as the attendees—prompted a reflection. Ustadh Ubaydullah EvansThe American Learning Institute for Muslims (ALIM) condemns in the strongest possible terms the violence that has been perpetrated against the Palestinian people by the Israeli regime and its enablers. It is at once harrowing and humiliating for the American community to watch passively as the lethal machinery of modern warfare is deployed against a defenseless, civilian population. Contrary to some uninformed opinion, ALIM has never defined itself as apolitical or quietest. Over our more than twenty year history, ALIM has offered an unrestricted platform to our faculty and guest contributors. This means we’ve learned from scholars and activists who have broadened the scope of our political awareness, challenged us to identify with the oppressed, and agitated concerning our complicity with injustice. Stated unequivocally, solidarity with our brothers and sisters suffering oppression is a core tenet of our faith. As such, to deny the imperative of advocating for them would violate our mission of empowering the American Muslim community through literacy. What Islamic literacy can our community claim if we fail to recognize the centrality of condemning injustice to Islam? How can our community claim empowerment if we can’t voice disapproval with the fact that our tax dollars are used to fund the unjustifiable deaths of our co-religionists?

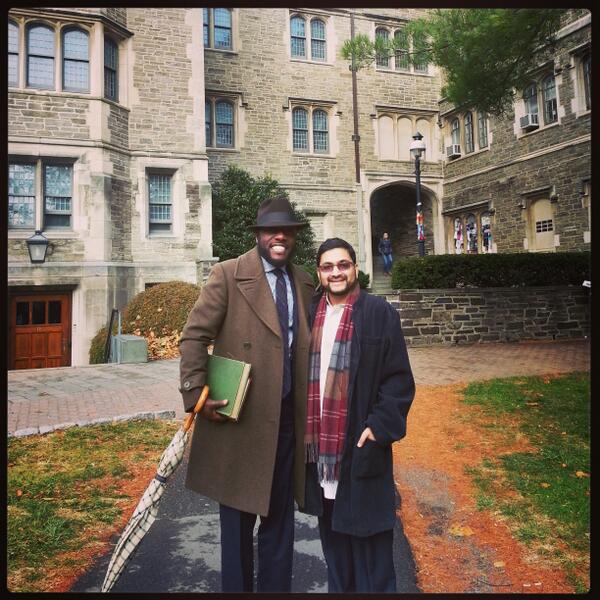

Ustadh Ubaydullah Evans"Souls are like conscripted soldiers. Those familiar with each other get on easily while those who don’t know each other feel mutual estrangement.” From the very moment Imam Sohaib Sultan and I met we got on with easy familiarity. Something about his posture and demeanor immediately disarmed me. Usually, a kind of ritual “feeling out” takes place when Muslims with public profiles meet. In addition to the semiotics regularly associated with dress and presentation; the manner in which a person deploys classical Arabic, the scholars they cite, their take on certain contemporary issues, etc. places them in some category or another: Traditional, progressive, Sufi, reformist, liberal, conservative, woke, apolitical…whatever. My encounters with my brother Sohaib were never degraded by the issuance of such litmus tests. We always spoke as friends.

Ustadh Ubaydullah Evans“The Third Resurrection” refers to Blackamerican engagement with the scholarly

tradition of Islam. It is not simply about learning the tradition. To be sure, classical training is an essential point of departure. However, the Third Res, cannot be realized until we deploy tradition in ways that are both authentic and relevant. This requires a subtle balance. On the one hand, tradition places a premium on precedent and on the other, many of the realities confronting Blackamerican Muslims are unprecedented. Ustadh Ubaydullah EvansI was actually in a relationship when I decided to embrace Islam. Not only did I not assume any tension between my relationship and newfound religious beliefs, I was proud of both! So it wasn’t uncommon, on the Fridays we didn’t have school, for me to invite my girlfriend to the mosque. And although she could never quite summon the nerve to enter, we’d often stroll about arm-in-arm afterwards; checking out the various vendors and their tables. Thinking back to that time, all I can say is: If I WAS doing something wrong, no one would’ve been able to guess. I walked as confidently among the community as I would have if she and I had been married. Now that isn’t to say, at that time, my girlfriend and I were doing other things married people do. I was familiar with abstinence as a religious virtue. In fact, among all the different social groups that existed within my high school, there was a group of popular, attractive, very outspoken evangelical Christian girls. They dressed modestly, threw their own chaperoned parties or attended the parties of others as a group. Perhaps the most curious thing about them was that they all wore rings on their ring fingers. And it seemed like they never missed an opportunity to hold up their left hands and tell all the hormonally charged young “heathens” lusting after them that sex would only happen, “when this ring is replaced by a wedding ring.” In retrospect, I can see their profound impact on me. They had chastity rings, an admirable solidarity, and they were completely unapologetic about who they were. As silly as it sounds now, for me, those young girls represented the ne plus ultra in terms of religious commitment as a teenager. And even they dated! It was normal to see one of them at homecoming with some clean-cut type who shared their conviction. Or you would see them at the movies with one of “the guys” who had been feigning an interest in devotion so he could test their virtue—only to report some hand-holding and maybe even kissing but ultimately, “that she wasn’t budging.” Hence, after embracing Islam the highest ideal of piety I could imagine was “not budging.” But there wasn’t anything wrong with hanging out. At that point, I’m not sure I understood there was anything wrong with making out. Just don’t have sex before marriage.

Last week over dinner, Aasiyah, my fourteen year old, announced to everyone: “I’m never going to have children!” The initial response that formed in my head was, “I totally feel you but unfortunately it’s too late for me!” Trying to outdo a teenager in sarcasm is both futile and inadvisable so I settled on a sympathetic, “why not?” “What’s the point?” she retorted flippantly. I felt a strange sensation: On the one hand, I knew that she, like the rest of us, had been confined to the house chasing her younger siblings for the past nine months. We were hearing frustration with Najashi and Makeda, I thought to myself. On the other, this was actually a good question—one that I had never really considered…

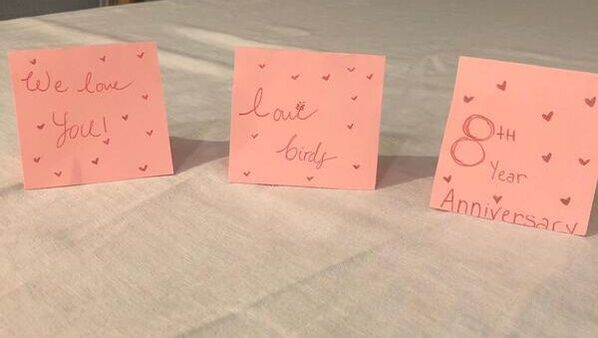

What is the point? I’m not sure there is a definitive answer. However, it is important for us, as parents, to be anchored somewhere. When the task becomes difficult, as it most assuredly will from time to time, our fortitude is the direct consequence of the meaning we give to parenting. As such, I try to remember what one teacher many years ago mentioned about the Qur’an. After offering many disclaimers to ensure he wouldn’t be perceived as irreverent, he said, “The Qur’an, in all of its astounding beauty, is really a book about dysfunctional families.” The lives of the Prophets of God and the righteous (upon all of them be peace) are examples for us. The Islamic doctrine of ‘iṣma (to be divinely protected from committing willful sins), which is shared by both Sunnis and Shi’is, maintains that the Prophets (upon them be peace) represent the highest moral possibility for human beings. And yet, when we look at them, we see lives that were not only unable to avoid familial conflict, but were, as a matter of fact, defined by it. What are we to say about Abraham (upon him be peace) and his well-documented struggle with his father—which resulted in the latter making an attempt on his son’s life. The sons of Adam, Cane and Abel (Hābil and Qābil); what are we to make of the bloodshed between them? What can be said of the blessed Aasiyah (upon her be peace), the wife of Pharaoh, who disavowed the evil of her husband? Joseph (upon him be peace) suffered an attempt on his life at the hands of his brothers. For that matter, Jacob (upon him be peace) was deceived by his sons and made to believe that his dearest son had been killed in an accident. The marital difficulties of both Job and Lot (upon them be peace) are visited in the Qur’an. And perhaps most relevant to us here, what are we to make of Noah’s (upon him be peace) inability to ensure the safety of his son and guide him to salvation? We encounter the Divine through our relationships with those closest to us. Family teaches us many lessons. In the case of children, perhaps the most important lesson we learn is tawakkul (reliance upon God.) To be sure, we are reminded that even personal piety is not the outcome of merit but rather grace. Nonetheless, the secret of free-will creates within us the sense that we enjoy a locus of control with regard to the personal. With kids…all bets are off! One is keenly aware that God is in control at all times. Hannah (upon her be peace), the mother of the Blessed Mary (upon her be peace) prayed, {“…O my Lord, I have vowed to You what is in my womb, to be dedicated to Your service, so accept this from me. Indeed, You are All-Hearing, All-Knowing.’ Then when she delivered her (Mary) she said, ‘O my Lord, I have delivered a female,’ and God knew best what she had delivered, ‘And the male is not like the female, and I have named her Mary, and I seek refuge with You for her and for her children from Satan’”} [3:33-36] Hannah solicits God for protection for her daughter and for her daughter’s children as Mary (upon her be peace) is still an infant. Her prayer is answered, {“So her Lord fully accepted her, and gave her a good upbringing and put her in the care of Zechariah…”} [3:37] In the verse, the good upbringing of Mary is attributed to God. This in no way absolves us of responsibility to our children; however, it is a potent reminder that matter is not entirely in our hands. The farmer must apply himself with both skill and industry when planting but it is God that causes the seed to grow: {“Have you considered what you plant? Is it you who cause it to grow, or is it we who do so?”} [56:63-64] {“Our Lord, Grant us the delight of our eyes in our spouses and children and make us leaders of the pious”} [25:74] The Quran also anchors “the why” of parenting in the immense delight and reward that are experienced in children. Accomplishment is always vindicating. One may attain a professional degree, successfully launch a company, build something beautiful with your hands, obtain something that you’ve longed for, etc. However, nothing approaches the joy of seeing your children become people you admire. My wedding anniversary is on New Year’s Eve. Brothers, this is forgetfulness insurance! Usually, Hadiyah and I plan an experience and the kids either go to grandma’s house or are placed with a sitter. This year, as I’m sure everyone knows, nothing follows precedent. So for the first time in eight years, my wife and I prepared to celebrate our anniversary and bring in the New Year loafing around in pajamas all day and buying the kids confetti and noise makers from Party City. It won’t be the beaches of Trinidad or a bed and breakfast on Lake Geneva, but at least we’ll be able to bring in the New Year with the kids, we said. To my surprise, when I returned from a morning workout, I saw all three of my children dressed in formal clothing, milling about the kitchen. Aasiyah instructed me to get cleaned up and to return for breakfast “dressed fancy.” With me, the dress fancy part registered instantly but I was still trying to figure out everything else! Once upstairs, my wife explained to me that the kids had awakened her with a hand-illustrated menu and were treating us to a surprise anniversary breakfast. Subhanallah, the preparation was done with so much good taste and attention to detail that at some point I remember thinking to myself, “Did my children do this? Wait a minute, can my children do this!?” After breakfast, Hadiyah and I were led away to the basement and treated to manicures and spa treatments. Here’s an anecdote: While massaging my shoulders, Najashi, my precious six year old son, hilariously said to me in a soothing voice, “Think about things that make you happy. Think about when you had hair!” After an intermission, they served us dinner and this was undoubtedly the piéce de résistance. By this point, I was completely “bought-in” and dressed in black-tie while Hadiyah accompanied me in a formal dress. My children had shown so much competence and character in putting this day together—and in the midst of a pandemic!—and we wanted to honor their efforts. Aasiyah had arranged for us: shrimp fettuccine, freshly baked French bread, Cesar salad, a wide assortment of our favorite sparkling drinks, and our favorite chocolate torte for dessert. During the meal she handled all the service and even acted as our halal sommelier—keeping our glasses filled but without impeding the conversation for the duration of the entire meal. I was floored. My eldest had led her siblings in honoring and serving their parents, esteeming and elevating marriage/family, and displaying the competence, generosity, and consideration required to flawlessly execute such an exquisite day. Unequivocally, I say, it was the best wedding anniversary we’ve had yet. Of course, I can’t take any of the credit! Aasiyah is learning from my wife and some of the phenomenal sisters Hadiyah has brought into her orbit. Nonetheless, my eyes are cooled just the same. This is why I wanted to have children. Aasiyah, I pray that you one day have children that make you as proud as you’ve made me. Dad Chicago 2021 One of the most insightful religious reflections I ever heard was mentioned by an atheist. During the Q and A that directly followed my lecture, a questioner from the audience rose to speak. He was a middle-aged white man of slender build, dressed in business casual clothing (chinos and a plaid button down shirt), and wearing glasses. I got the sense that he was faculty at the small college at which I was presenting. After thanking me for my remarks, which, if I recall correctly, were about Islam and Post-Modernity or something like that, he sought my permission to venture slightly off topic and ask a ‘personal’ question. Not knowing what to I expect, I forced a laugh and said, “well, it depends how personal.” After granting him permission, he identified himself as “an atheist but a seeker,” he then said, “I thought your remarks about religion were balanced. I’m clear about your conviction but it didn’t appear that you were attempting to evangelize [sic] the audience. I feel compelled to ask, what is the most challenging aspect of being a person of faith in the modern age?” The question was pithy and I don’t think any non-Muslim had ever posed it to me in such direct fashion. This wasn’t my dinner table, this was a stage. And the man wasn’t a Muslim that had grown weary of the rose-tinted, plastic idealism of religious scholars and instead wanted some emotional vulnerability and personal testimonial; he was a seeker who didn’t believe in God. In any other context, I probably would’ve disclosed some of my spending habits and the inadequate sensitivity to the suffering of others that allows me to spend money as I do. However, I knew he wanted something different. My mind raced, “c’mon, Ubayd. Say something brilliant, something edgy, something thoughtful.” I dug into the most honest place I could find in that moment and finally said, “Progress and moral evolution. I adhere to a 1400 year old tradition that contains both metaphysical and moral insights. Some of those moral insights are based on assumptions about things such as sexual propriety, the viability of warfare and violence, hierarchies among human beings (human bondage), etc. which have very different analogs among progressive thinkers today. I struggle to be true to my tradition in letter and spirit, while being critical of different modes of progressive thought, and affirming Islam’s commitment to alleviating human suffering.” I don’t know what the heck that was but it was the best I could do! I laugh as a type this now because I can recall him looking at me confusedly and offering, “thank you.” My answer was underwhelming and I could tell that he hadn’t been sufficiently engaged so I turned the tables: “Now, may I ask you a similarly personal question?” He nodded in the affirmative so I continued, “What is the most challenging aspect of being an atheist in the modern age?” En garde! I took him by surprise and I appreciated the fact that I had—perhaps a little too much! The university campus has become a place that celebrates and promotes “atheisizing” and secularizing epistemologies in the same way religious communities celebrate faith. Except that while religious folks are usually candid about doubt and lapses of faith and “dark nights of the soul”, non-religious folks tend to speak of unfaith as a singular source of clarity and liberation. He had to think. After a long pause, he poised himself and said, “Gratitude. I struggle with gratitude. I’ve been the beneficiary of such great privilege and good favor in my life and yet I don’t believe in anything to which I can attribute that favor. To call it merit is a lie. To call it luck is unsatisfying. And to act as though I don’t feel it is like being a psychopath. I honestly don’t know what to do…” I sat frozen. In fact, I think the whole room fell silent. It was one of the most honest things I’d ever heard anyone say. And there was no “storybook” ending. I didn’t grab the mic and talk about the Arabic term dīn (faith) and its etymological connection to the word dayn (debt). I didn’t share the Qur’anic verse in which Satan himself declares: {“Then I will come to them from the front and from the rear, and from their right and from their left. And You will not find most them thankful.”} [7:17] I didn’t even get a chance to thank him for opening a new window into my understanding of faith. He exited the auditorium before the conclusion of the session. Just an imperfect and utterly human attempt at saying, “thank you.” This is the essence of faith. It makes sense then that the antonym of the Arabic term “kufr” (disbelief) is not imān or faith but rather “shukr” (gratitude). While a student at al-Azhar, I stumbled across Alister McGrath’s book In the Twilight of Atheism. The Oxfordian theologian investigated the Freudian claim that belief in God is an illusion based on an infantile need for a powerful father figure. In response, McGrath mused about Freud’s inability to view atheism through a similar lens. In other words, if belief is just the product of arrested human development, how should we understand disbelief? Perhaps disbelief is based on a similarly infantile need to feel autonomous—McGrath’s insight was particularly profound given Freud’s own writings concerning developmental psychology in children. Nonetheless, “illusory autonomy” or istighnā’ is a core Qur’ānic concept. In the first revelation received by the Prophet Muhammad (upon him be peace), the Almighty proclaims: {“(1) Read! In the name of your Lord and Cherisher who created. (2) Created man out of a clot of congealed blood. (3) Read! And Your Lord is Most Bountiful. (4) He Who taught (the use of) the Pen. (5) Taught man that which he knew not. (6) Nay but man transgresses all bounds. (7) In that he looks upon himself as self-sufficient. (8) Indeed, unto your Lord is the return of all…”} [96: 1-8] We are entirely contingent beings. If COVID-19 has shown us nothing else, it has shown us that. Some time ago, Dr. Sherman Jackson provided me a thought-provoking insight. In paraphrase, he mentioned that we do ourselves a disservice by making God the point of departure when engaging secular thinkers. If we instead, he asserted, began with our indisputably shared experience of human contingency, we might clarify the basis of our faith more effectively. I was lost too so don’t feel bad! He gave an example: If someone expected one of their loved ones home by 9pm and hadn’t heard from them well past that, they might grow concerned. If such absence was uncharacteristic of the loved one, by 3 or 4am they’re anxiety would be heightened. In that moment, Dr. Jackson mentioned, some people will pray. Some others might pace nervously. Some will sweat profusely and bite their nails. Others might pour a stiff drink. Some might do all of the above! However, all of them, in that moment, realize their contingency. They all realize that the outcome required to return their peace of mind is not in their own hands. In that moment, self-sufficiency makes no promises. In other words, Dr. Jackson was saying that belief in God is but one of many possible responses to the anxiety that results from recognizing the limited control we ultimately exert over our existence. Not all choose to manage through faith in God but all must choose some means of managing. This unites us as human beings. When the beloved finally makes it home, safe, sound, and without incident, all are relieved. Faith, however, is embracing that nearly irrepressible impulse to say, “thank you,” and it’s incredibly satisfying. The questioner at the university was articulating the dilemma of having an innate sense of providence but not believing in God. And it really appeared to be affecting him. It was one of the first times I thought about how thankful I am being able to give thanks. Ubaydullah Evans Chicago 2020 Most classical articulations of Islamic law are unanimous concerning the prohibition of Muslim women marrying non-Muslim men. Sūrat al-Mumtaḥana declares, {“…These women are not lawful wives for the disbelievers, nor are the disbelievers lawful husbands for them.”} [60:10]. This was revealed about Muslim émigrés to Medina that were married to Makkan polytheists. However, consistent with the Islamic legal maxim which states, “Interpretive consideration is given primarily to the general import of a text, not the particular event that occasioned the text.” (al-‘ibra bi ‘umūm al-lafdh wa laysa bi khuṣūṣ as-sabab), the verse became the basis of a general prohibition of interreligious marriage between Muslim women and non-Muslim men. Conversely, on the basis of the following verses in Sūrat al-Mā’ida: {“…Lawful unto you in marriage are (not only) the virtuous women of the believers but also virtuous women from among those who were given the Scripture (Jews and Christians) before your time…”}[5:5]

Muslim men were granted permission to intermarry with Jewish and Christian women. This allowance is not extended to Muslim women; neither in the scriptural sources nor the compendia of positive law. One would expect a ruling which expresses such a clear gender bias to generate a great deal of debate within the tradition. Yet, it doesn’t appear that much ink was spilled by classical scholars concerning the issue. The lack of engagement here is likely an indication that the assumptions concerning gender and/or marriage, which underlie these rulings, are either considered essential or consistently demonstrable. Within our community, many women have begun to question this ruling. Although I wish I didn’t have to, it’s important to highlight the devoted and informed nature of the questions being posed. Too often those deferential to tradition are unable to treat the questions, concerns, and critical insights of Muslim women with integrity. Yes, it is true that we live in a context in which revealed religion in general and Islam in particular is under heavy assault by philosophical liberalism. However, a Muslim woman asking questions through which she hopes to gain clarity about her faith is not engaged in a covert or unwitting attempt to destroy traditional Islam! As mentioned, scholars’ intellectual output on this issue is surprisingly limited. Nonetheless, the protection of faith is the most consistent reason offered for the prohibition. The idea being: a Muslim woman marrying a non-Muslim man would be placed in a precarious position with regard to the free exercise of her religion. Ironically, the nature of this precariousness is never really spelled out. It appears that pre-modern scholars understood “something” to be a given and their modern-day successors agreed. Was the source of that presumed precariousness legal? Islam recognizes not only the right of a Christian or Jewish woman married to a Muslim man to practice her faith, but also identifies each of those traditions as emanating from authentic Prophetic messages. In other words, a Jewish or Christian woman married to a Muslim man enjoys legal protection to exercise her faith AND a presumed modicum of respect for her prophets and religious tradition. Perhaps for classical scholars, the Muslim woman in a similar circumstance was presumed to enjoy neither. This reason would mean that the difference in the two rulings on intermarriage for men and women only secondarily involves gender. The primary difference involves understandings of tolerance within the respective religious traditions. Or is the assumed precariousness practical? The Qur’ān states {“Men are the caretakers of women. Men have been provisioned by God for the task and bear the responsibility of financially supporting women. And righteous women are compliant and when alone, protective of what God has entrusted them with…”} [4:34] This verse portrays the husband providing the foundational care and support upon which the couple’s life together is built. Our context—where there is much concern about hierarchy between men and women—will undoubtedly impact the way we read the compliance expected from wives in this verse. Unfortunately, some men and women in our community imagine this verse to refer to “the man” at the top handing out orders to his faithful ward. God help us. In fact, the opposite is true. This verse envisions the husband at the base, responsible for contributing foundational security and comfort. Upon that foundation, both husband and wife make other qualitatively more important spiritual and emotional contributions to their lives together. However, the nature of a base or foundation, of anything, as a matter of fact, is that it delimits and determines the character of what can be built on top of it. In other words, the verse cited above expresses a framework for marital harmony: The contributions of wives to their families are expected to be compliant or consistent with the material foundations provided by their husbands. This is the Qur’anic ideal regarding marriage. Upon that ideal, it’s easy to understand how a Muslim woman could be potentially compromised by having a non-Muslim husband. For example, what if her husband decides to own vineyards and sell wine for their livelihood? Would she be expected to comply? Can she, as a Muslim, build her life and make contributions to her family upon such a foundation? This might be the precariousness classical scholars had in mind when upholding this prohibition. Within this reason for the preponderant ruling, i.e., that it is impermissible for Muslim women to marry non-Muslim men, gender is effective. However, it is not through the lens of essential masculine and feminine archetypes but rather socially contingent roles. I’m using the term “essential” masculinity and femininity to refer to the perspective of those who understand the verse, {…”and the male is not like the female…”} [3:36] to refer to more than the different roles into which we’ve been socialized. Rather, this view maintains, there are primordial or natural differences between men and women that make it inadvisable for Muslim women to marry non-Muslim men. It’s likely that some will take exception to this view. It has very bad company. Historically, the most horrendous “self-serving, other-obliterating” ideologies, theories, beliefs, etc have been justified by citing “natural” differences. French sociologist Robert Hertz said it well, “Every social hierarchy claims to be founded on the nature of things. It thus accords to itself eternity; it escapes change and attacks the innovators.” However, to my mind, the most effective way to counteract toxic hierarchies is not by accepting the positive value of the characteristics of those at the top and then proving, “we’re that way too.” This could result in self-obliteration. Rather, it involves taking stock of oneself and affirming the positive value of your distinctiveness. In the context of offering a reason for the traditional ruling on intermarriage between Muslim women and non-Muslim men, Muslim women must take stock of themselves. Some of the ‘natural difference’ arguments might be regarded as inaccurate while others resonate. For example, an argument which states that a woman is so predisposed to following the example of her husband that just the act of marrying a non-Muslim man will remove her faith in God and His Messenger (upon him be peace) may be false. On the other hand, the idea that women derive greater satisfaction from group activity within families and are more adversely affected by its absence than men could be relevant. “A ruling necessarily follows the existence or absence of its reason” (al-ḥukmu yadūru ma ‘illatihi wujūdan wa ‘adman). In Islamic law, when looking at transactions (muāmalāt)—as opposed to acts of worship (‘ibādāt)—this maxim is cited often. In regard to the ruling that religious intermarriage is impermissible for Muslim women the reason given is protection of their integrity. The question is “protection from what?” In each of the scenarios we explored it’s easy to imagine how women might no longer find those reasons determinative. The right to freely exercise religious conviction is the first amendment of the US Constitution. American Muslim women enjoy legal protection to practice their faith and many progressive Jewish and Christian denominations have developed broad, ecumenical approaches to their respective traditions which reserve a place of honor for Islam. Additionally, there has never been a time in which men were the breadwinners in all families. In America today this is probably less common than ever. Families are structured in ways in which financial responsibility is shared. Many women no longer rely solely on their husbands to provide religiously acceptable livelihoods. And the arguments about essential masculinity and femininity impacting intermarriage are either something one accepts or not. On the whole, I submit that all of this is probabilistic. However, on account of the classical scholars unanimity on this position, the possibility that the reason for this ruling is a ḥikmah ilāhīya (Divine wisdom) to which we lack access and my own religious conservatism, I personally would find no solace in departing from precedent as a general rule. Nonetheless, I aspire to be sensitive to the plight of my Muslim sisters who desire to be married but who are with extremely limited options among Muslim men. First and foremost, I commit to holding brothers responsible for getting our stuff together so that we can be husbands. Secondly, for Muslim women seriously considering this as an option, I encourage them to seek counsel through personalized legal responsa (fatwa). Perhaps scholars trained in iftā (the issuance of fatwa) will be able offer opinions which move beyond general rules and come closer to home. Ubaydullah Evans Chicago 2020 The topic of polygamy generates strong opinions: It is the resource we’ve yet to utilize in our response to the marriage crisis. It is a vestige of Islam’s checkered patriarchal past. It is expressive of the priority Islam affords family and community. It is a fig leaf used by undisciplined men to justify their philandering ways. It is the litmus test whose acceptance proves a woman’s embrace of the Prophetic way (Sunnah). It is an outmoded form of marriage which might work in other contexts but is doomed to fail in our own. It uplifts men by forcing them to spiritually and materially prepare for greater responsibility. It degrades women by exposing them to emotional harm. Attend a dinner party among Muslims and you’re likely to encounter all of these views. In my estimation, plural marriage is a unique aspect of the Sunnah. It was practiced by the Prophet (upon him be peace) and thus must have the potential for moral excellence. However, the Prophet (upon him be peace) was discerning in the manner in which he engaged the practice and thus it must be seen as potentially dangerous. This is an opinion-editorial; just another seat around the dinner table but (hopefully) with the added clarity offered by writing. This isn’t a sociological or anthropological treatment—I don’t have the resources or training for either. Nor is this, strictly speaking, a fiqhi treatment of the issue. Put simply, many American Muslim communities are witnessing an alarming trend: Single, religiously-adherent, adult women are having a hard time finding partners for marriage and polygamy is increasingly being discussed as an alternative. To be sure, polygamy is no silver bullet. The only long-term solution is resuscitating our communal commitment to marriage and growing our young men in focus and capacity. Nonetheless, for people who don’t have the luxury of waiting for the paradigm to shift, plural marriage may represent a source of hope.

The prospect of polygamy in our community presents numerous questions. For starters, it’s illegal. Well-reasoned arguments that Muslims are religiously obliged to obey the ‘law of the land’ notwithstanding, there are those who deem marriage a personal, religious matter and regard government sanction therein as irrelevant. However, the monogamous ideal is still part and parcel of our society. In the Qur’an, God describes marriage as a mithāq ghalīdh (contract of grave importance). Contracts of this level of gravity are rarely without guarantors. Many of us would scoff at the prospect of purchasing an automobile much less a parcel of land with a simple handshake and gentleman’s agreement. With regard to marriage, the provisions of Islamic law and those of American civil law are not perfectly complementary. However, they do share some provisions such as health care power of attorney and inheritance. In the case of a single marriage, some version of these rights can be guaranteed for each party if the union is registered in civil court. A second Islamic marriage, by comparison, couldn’t enjoy the same protections. To my mind, this doesn’t preclude the possibility of plural marriage among Muslims in the US. However, it does mean that securing even a modicum of the rights Islamic law guarantees the second wife would require potentially costly, intentional engagement with the legal system. Other considerations such as insurance (health/auto/life), tax filing, etc also presume a monogamous ideal. These are secondary concerns but they highlight an important point. Comedian Azhar Usman once joked, “Only two kinds of Muslims actually practice polygamy…rich Arabs and poor African Americans.” This old bit hasn’t aged well. The racial/ethnic stereotypes which carry it are distasteful. Nonetheless, if we excuse that part of the joke on account of its age, it reveals an important aspect of this conversation. When one factors all the costs entailed by an additional marriage in terms of housing, education, child-care, health-care, food, auto, recreation, etc. you’ve narrowed down the pool of those eligible considerably. It’s easy to imagine a wealthy family absorbing those costs. And likewise, it’s hard to imagine a middle-class family—for whom generational upward mobility is priority—absorbing those costs. Though counterintuitive and even objectionable to some, much of our community’s current engagement with polygamy exists within working-class and struggling communities. The idea being that for some people marriage is primarily about chastity, companionship and fulfilling the rights of their partners to a religiously acceptable degree. The prospect of not being able realize such goals as home ownership, private school enrollment, diverse capital investment, annual vacations, college tuition payment, etc. are not things that would dissuade them from marriage—whether monogamous or polygamous. Any serious consideration of polygamy within our community would entail the same implication. Families would either need to raise their earning profile so as to comfortably absorb the costs of an additional marriage or adjust their expectations with regard to lifestyle. What this adjustment would mean to some segments of our community, in light of its mission to confront social ills like chronic, generational, poverty and economic injustice, is something to be considered. True to the saying, “No romance before finance,” I began with a few reflections on the financial implications of plural marriage. Of much greater concern, I presume, to most people, are the romantic/interpersonal implications of polygamy. In a culture as deeply monogamous as our own, it’s difficult to point to morally inspiring examples of men in plural relationships. For many men, this means the archetype they most readily associate with polygamy is not the Prophet (upon him be peace) or the tireless family man pulling double duty. Rather, it’s the ladies’ man, the player, the pimp, etc. Similarly, for many women, it’s the cheater, the adulterer, the philanderer, the Lothario. This makes it nearly impossible for men or women to view polygamy with integrity. Quite the reverse, given the lack of morally inspiring examples, almost by default, second marriages are rarely seen through the same family-affirming, responsibility-assuming, pleasure of God-seeking lens through which we generally view marriage. Many of us are either married or know people that have gotten married. And although there is always recognition that marriage will make (mutually desired) intimacy between the couple permissible, it usually isn’t treated as a singular focus. There’s an acknowledgement—especially for married people—that the newlyweds are voluntarily committing to a relationship that will demand their absolute moral best: devotion, patience, dedication, sacrifice, service, a willingness to forgive, and a readiness to rear children. The two Muslims committing to marriage have taken their natural affinity for one another to the moral summit of romantic relationships, and for that we admire and commend them. However, when a family decides that the time is right for the husband to make that commitment a second time, that subsequent union is scarcely treated with the same respect and integrity. It’s from the Prophetic way, why not? Is it the overwhelming prevalence of bad examples of men who, in actual fact, have engaged such partnerships with little integrity or responsibility? Do we assume that within a culture of monogamy a woman whose husband marries a second time will inevitably feel betrayal, embarrassment and humiliation? Is it because the stereotypes of families engaged in plural marriage are things some of us don’t respect: poor, Black, urban, and Salafi in religious orientation? Or is it because we fear lending credence to Western depictions of Islam as a religion of sensuality and unbridled carnality? I don’t know the answer to this question. However, I do feel it is the barometer which measures the maturity and seriousness of our community concerning the topic. Any marriage that can’t be regarded with integrity and viewed as an expression of a Prophetic, morally inspiring ideal—and not that of players or cheaters—will have little success among Muslims. Ubaydullah Evans Chicago 2020 A wide assessment of the marriage prospects of women within our community reveals a crisis. There is a paucity of eligible bachelors and this is an ominous sign. Buoyed by misleading statistics which casts Islam as the “fastest growing religion in America” (this is true but certainly not because of conversion or sustained religious commitment. Rather, on average Muslims tend to have more children than their Jewish or Christian counterparts) and a delusional sense of permanence, we have failed to take stock of the threat of discontinuity facing Islam in America. A 2017 Pew research study found that nearly 23% of Muslims in the US grow disaffected with the religion by the time they reach adulthood. That’s nearly 1 in 4. Without the benefit of hard data there’s no way of knowing for sure but I’d be willing to bet on a strong correlation between commitment/disaffection with Islam and intimate partner choice/accessibility. To be sure, there have been minority Muslim communities who failed to maintain distinct identities due, at least in part, to exogamy (marrying outside the community). This issue deserves a thorough treatment. A blog piece of 1500 words, even an overambitious one (wink wink) can offer nothing beyond impressions. Nonetheless, we would like to initiate some conversation: In light of the current situation, should we explore wiser ways of discussing the centrality of marriage to Muslim religious life?

A social phenomenon is the consequence of many factors: economic, cultural, religious, etc. In spite of the heterogeneous make up of our community, can we pinpoint any overarching trends? How might we approach responding to this challenge? As the saying goes, “We didn’t get into this overnight and we’re not getting out of it overnight.” When proposing solutions to the marriage breakdown, people tend toward boldness. This is productive. Some say we should arrange marriages among our youth while they’re teenagers. Some cite the Prophetic practice of plural marriage as a potential means of addressing this situation. Others maintain that the prohibition of interreligious marriage for Muslim women is based on outmoded notions of gender hierarchy and should be discarded so that Muslim women can pursue marriage with eligible Christian and Jewish men in addition to Muslims. Prophetic record and practice indicate a clear priority given to the value of excellence in relationships over other modalities of religious devotion. The Prophet (upon him be peace) forbade monasticism, corrected a young man who assumed celibacy more expressive of high spiritual aspiration than marriage, and taught that marriage is half of our faith. This is undeniable. Yet, religious messaging that makes marriage the sine qua non of faith is potentially irresponsible—especially in our context. What is to be said of John the Baptist and Jesus Christ (upon them be peace), at-Ṭabarī, Rābia al-Adawīyya, an-Nawawī, Ibn Taymiyya, or the companion who was dragged to the Messenger of God (upon him be peace) by her father. In his homiletic compilation, at-Targhīb wa at-Tarhīb, al-Mundhiri cites an interesting tradition of the Prophet (upon him be peace): “A man came to the Prophet dragging his daughter by the arm, complaining that she had no interest in marriage. He expected the Prophet (upon him be peace) to chide his daughter. Instead of encouraging her to get married, the Prophet (upon him be peace) simply asked: ‘Why don’t you have any interest in marriage?’ ‘Before gauging my interest in marriage,’ said the young woman whose composure and poise can be sensed from the text, ‘I would need to know exactly what marriage entails.’ After the Prophet explained the contractual dimension of marriage to her, she exclaimed, ‘I will never have that kind of responsibility to any man!’ turning to address the woman’s father at this point, the Prophet (upon him be peace) said, ‘She’s made her decision. You shouldn’t force her.’” There was no mention of anything wanting in this woman’s adherence to the teachings of the Prophet (upon him be peace). The young man alluded to earlier erroneously assumed celibacy a superior expression of faith than marriage and he was swiftly corrected by the Prophet with his words: “…Who are these people? Whoever desires something other than my way is not from me.” Conversely, this woman appears to have no interest in such grand claims. She’s simply stating marriage isn’t for me. And that’s ok. For sure, there are vast differences between a woman who doesn’t have any interest in marriage owning her truth and living it boldly and a woman who wants to be married and can’t find a suitable match. What they share, however, is that neither of them is married and neither is deficient or inadequate in any way. For such individuals, perhaps being free of the responsibility of marriage will open them to other forms of encounter with the Divine. Many Muslim singles have personally confided in me that they feel depressed, religiously adrift, purposeless, etc. because they are single. Loneliness is real and it would be a reprehensible form of spiritual bypassing to assume a one-off scriptural reference held together by admittedly tenuous thread capable of removing the lack of fulfillment and even sadness being alone may contain. Scripture should not be used to blot out human emotion. However, knowing that nothing is religiously wrong with me because I’m not currently married might make patient perseverance a little less unnerving. As stated, the reasons underlying the current crisis are multifarious, complex, and dynamic. Given the tremendous diversity within our community, it’s extremely difficult to generalize. For instance, Blackamerican Muslims (women and men) face disproportionate levels of discrimination in areas of education, employment, recidivism, etc. It goes without saying that these factors can militate against one’s ability to start/maintain a family. Addressing this specific challenge will involve continuing to develop visions of community which intentionally aim at mitigating the impact of these factors. Muslim women from second and third generation immigrant backgrounds still confront the phenomenon of in-group males marrying from “back home” or exclusively seeking partners that are younger and less accomplished. How can this coexist with a culture that encourages academic achievement and professional appointment for women? Undoubtedly, this requires the renegotiation of certain priorities. However, as far as overarching trends go, in my estimation, the most consistent issue contributing to the breakdown of marriage within our community is our inability to create a culture that really esteems marriage. By now, we have to face it. Marriage is no longer the exclusive or even preferred means of experiencing emotional and physical intimacy with a partner. Dating and now, hook-up culture, offer other forms of relationship; many of which are not nearly as public or demanding as marriage. Yes, for the devout it’s not merely the physical and emotional intimacy promised by marriage which makes it desirable. It is the grace of God. This is deeply inspiring and hugely problematic: Deeply inspiring because within a culture which doesn’t restrict romantic relationships to the marital bond, Muslims of conscience seek this responsibility for the sake of God. It’s hugely problematic because a culture of marriage can’t thrive if marriage is restricted to the devout. Once upon a time, family pressure and expectations of social conformity could shore up the places religious devotion failed to inspire a commitment to marriage. Those extraneous motivating factors haven’t lost all of their influence but a culture of radical individualism and decreased familial cohesion has weakened them significantly. In regard to motivating marriage, religious piety will continue to function as it always has. The crisis is the outcome of the waning influence of those secondary motivating factors. Marriage in our tradition is not a religious sacrament or just something one does to avoid sin. Deep and abiding friendship, financial advantage, wellness promotion, providing the stability required to achieve greatness, a reunification of souls that were together on the day of “Am I not your Lord,” the depth and beauty of a commitment to another person based on love AND MERCY, the opportunity to explore yourself through service to someone else, etc. traditional articulations of marriage in Islam contain rich conceptual frameworks. We must make use of these and many more, especially when counseling our young men, if we aspire to develop a culture that truly esteems marriage. Earning the pleasure of God and avoiding His wrath is the ultimate motivation for the Muslim, but in regard to marriage, it’s always had reinforcements. From polygamy to pragmatism (the suggestion that traditional positions prohibiting interreligious marriages for women are irrelevant or outmoded), responses to the current situation are varied and bold. Sacred Law contains limits but also much variety and boldness. Inshallah, our next post will provide an opportunity to explore the viability of some of these proposals. To Be Continued… Ubaydullah Evans Chicago 2020 The greatest liability of a good story is familiarity. Even the best stories are rendered a little less stirring with the passage of time and frequent repetition. Hakim Archuletta, a traditionally trained Islamic healer and homeopathy specialist, once described a good story as following life’s natural rhythm of contraction (qabḍ) and expansion (baṣṭ). The experience of listening intently, being wound up bit by bit, the tension (contraction) growing with the suspense, only to find relief (expansion) in the resolution is what holds our attention when listening to stories. As such, when suspense is lacking—because the outcome of the story is known—being present requires more intentionality. I’ve been told that the wheat is separated from the chaff among actors by a performer’s ability to completely act as if the story is unfolding before their character in real-time, in spite of their knowing the entire script. On Eid-Aḍḥā, we commemorate the willingness of Prophets Abraham and Ishmael (upon them be peace) to make the ultimate sacrifice in obedience to God. Yes, we know how the story ends, mashallah. However, by emotionally investing in the narrative and trying—as much as humanly possible—to go to a place where the resolution of the story hangs in the balance, we’re able to glean new insights and perspectives.

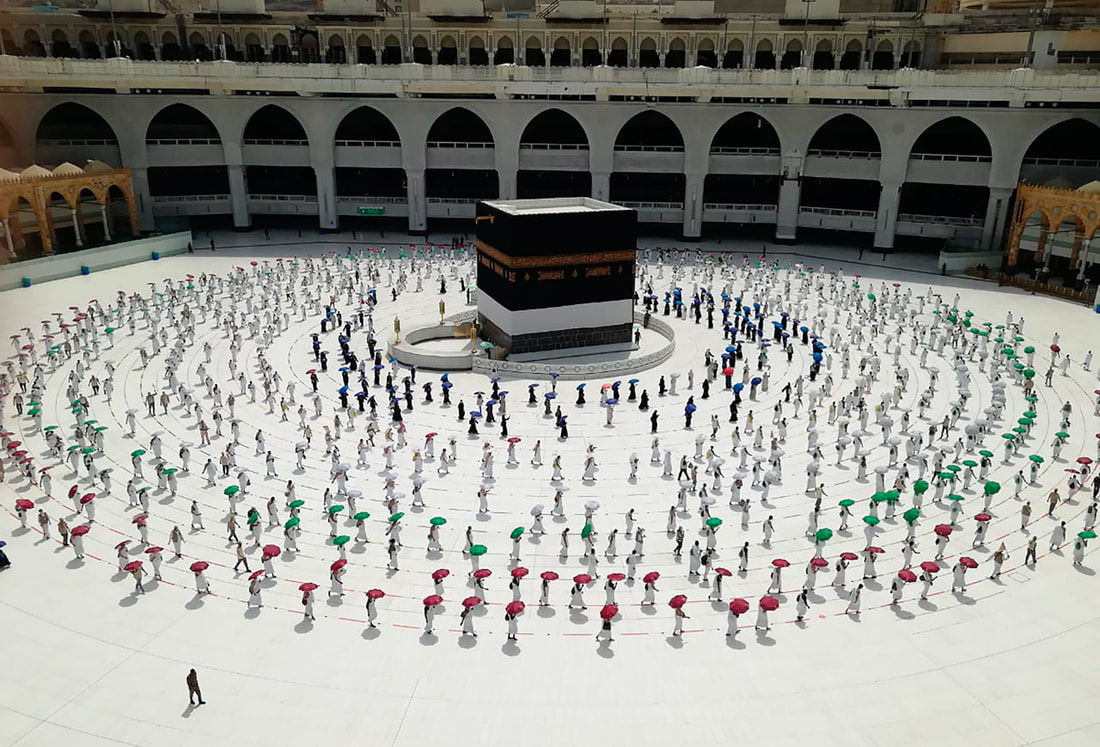

Abraham (upon him be peace) had a premonition in which he thought he took the life of his own son. Allow yourself to fully absorb the morbidity of that notion. Morally enriching what we find in scripture is essential. Take for instance, the following verses: “And kill them wherever you overtake them and expel them from wherever they have expelled you, and tumult and oppression are worse than killing. And do not fight them at the Masjid al-Haram until they fight you there. But if they fight you, then kill them. Such is the recompense of the disbelievers.” [2:191] “When the Inviolable Months have passed, kill the polytheists wherever you find them. Seize them, besiege them, and wait for them at every place of observation. If they repent, observe prayer, and pay the obligatory alms then let them go their way. Allah is forgiving, merciful. [9:5] They can either be read as proof that Islam sacralizes violence and is inherently incompatible with ideals of pluralism, tolerance, and conviviality or read as a limited set of directives for multilateral combat against a belligerent enemy. When teaching students to read the verses with the latter understanding our hope is that the moral enrichment of scripture becomes a part of their Islamic subjectivity. However, in the case of the story of Abraham and Ishmael (upon them be peace) the tendency to morally enrich the text can devolve into sanitizing the text, scrubbing it of feeling and real human emotion: “Abraham, the Prophet of God, had great knowledge of God. Therefore such a premonition wouldn’t have disturbed him. God wouldn’t torment someone by showing them a vision in which they slaughtered their own child. God is Merciful.” No. The story can only be appreciated when we realize that the premonition was absolutely harrowing. In fact, I can only countenance Abraham’s vision to sacrifice his son through a realization of who he was. The Qur’ānic narrative opens to find him ostracized by his community on account of pursuing the truth, disowned by his father and made the victim of a horrific attempt on his life, and forced to leave his family—essentially for dead—in a barren valley while clinging to God’s promise to provide for them. What was left for him to sacrifice? And yet, there is still an unmistakable reticence in Abraham’s tone when he addresses his son: “…O my son I have seen in a dream that I should sacrifice you; so consider what is your view…” [37:102] Again, all of his experience, even being thrown into a fire only to miraculously emerge unscathed couldn’t have prepared him for this. He doesn’t approach his son enthusiastically. Rather, he approached him cautiously. This is instructive for us. We tend to forget that in spite of their direct experience of the Divine, the Prophets (upon them be peace) and the righteous mentioned throughout the Qur’ān are human. Noah (upon him be peace) is clearly aggrieved about his son. Maryam (upon her be peace) is concerned about her reputation, and given the dictates of Mosaic Law, probably her safety after miraculously giving birth to Christ (upon him be peace). You can feel the anguish in Aasiyah’s (may God be pleased with her) words as she prays to God, declaring her innocence from Pharaoh and his blasphemy. Moses (upon him be peace) is being spoken to directly by God and yet is still worried about his welfare when he is commanded to liberate the Children of Israel and offer Pharaoh a chance to atone for his sins. These were real people. Faith didn’t insulate them from the frailties of human experience. Quite the reverse, faith gave them the ability to act in spite of. For most of us, a level of faith and certainty which can rise to the challenges of Abraham (upon him be peace) is unimaginable. That said, our challenges in faith, though much more mundane than sacrificing our children, can feel just as weighty. Comparison to Abraham is not intended to trivialize our challenges. Quite the reverse, reflecting upon the intensity of his sacrifice and perhaps most importantly the patience displayed by he and Ishmael awaiting God’s decree within the matter should be exemplary for us. Abraham (upon him be peace) is venerated by adherents of the Jewish, Christian, and Islamic traditions. Collectively, we are known as the “Abrahamic” religions. In the Qur’ān, God says, “Indeed, Abraham was a nation obedient to God, by nature upright, and he was not of the idolaters;” [16:120] Abraham rose to the challenges placed before him and consequently became celebrated for his virtue until the end of time. That reminds me of a conversation with a friend who was trying his hand at screenwriting for the first time. I asked him how it was going and he responded, “It’s one of the most spiritual things I’ve ever done.” “Subhanallah (Glory to God)!” I exclaimed. He appeared to be doing well but this certainly exceeded my expectations. Sheepishly, I followed, “how so? He then said, “I have these characters and I’m kind of in control of their destinies. And if I want to make a virtue of one of the characters known to the viewing audience I write trials and tribulations the character must overcome into his or her storyline.” Not quite making the connection, I shrugged my shoulders so as to indicate, “ok, and …” The aha moment came when he said, “Such is the case of Allah, Subhana wa ta’ala (Glorified and Exalted) with us.” And yet, Abraham (upon him be peace) couldn’t have known that his action would result in such esteem and celebration. He couldn’t have known that erecting the Sacred House at Bacca would result in that erstwhile barren valley becoming a site of pilgrimage for the nations of the world. Further, he couldn’t have known that his willingness to offer his son in sacrifice would result in an annual ritual of charity through which many of the world’s indigent enjoy provision today. There is no Tawfīq except by the permission of God and the end is always for those who are conscious of Him. Eid Mubarak! Ubaydullah Evans Chicago 2020 |

|

stay connected

PO Box 871785 Canton, MI 48187

(734) 956-0698

(734) 956-0698

2024 © American Learning Institute for Muslims. All rights reserved.

ALIM is a 501(c)(3) organization. All donations are zakat-eligible and tax deductible. Our EIN is 38-3633579.

Zelle: admin@alimprogram.com

Terms of Service | Privacy Guidelines | Sign Up for ALIM Emails I Get ALIM Text Alerts

ALIM is a 501(c)(3) organization. All donations are zakat-eligible and tax deductible. Our EIN is 38-3633579.

Zelle: admin@alimprogram.com

Terms of Service | Privacy Guidelines | Sign Up for ALIM Emails I Get ALIM Text Alerts

RSS Feed

RSS Feed